Complying with privacy law is crucial for any business operating online.

Due to the nature of online commerce and marketing, businesses often collect personal information from people in multiple legal jurisdictions. If you offer goods or services in a given country, you must obey the privacy laws of that country.

We've compiled information about the state of privacy law in some major markets worldwide. We'll be answering the following questions:

- What are the main privacy laws in each jurisdiction, and who do they apply to?

- How does the law define personal information?

- What are the requirements when conducting targeted online advertising using cookies?

- What are the requirements for collecting consent?

- What must businesses include in their Privacy Policies?

We've also provided links to English translations and further resources in each legal jurisdiction.

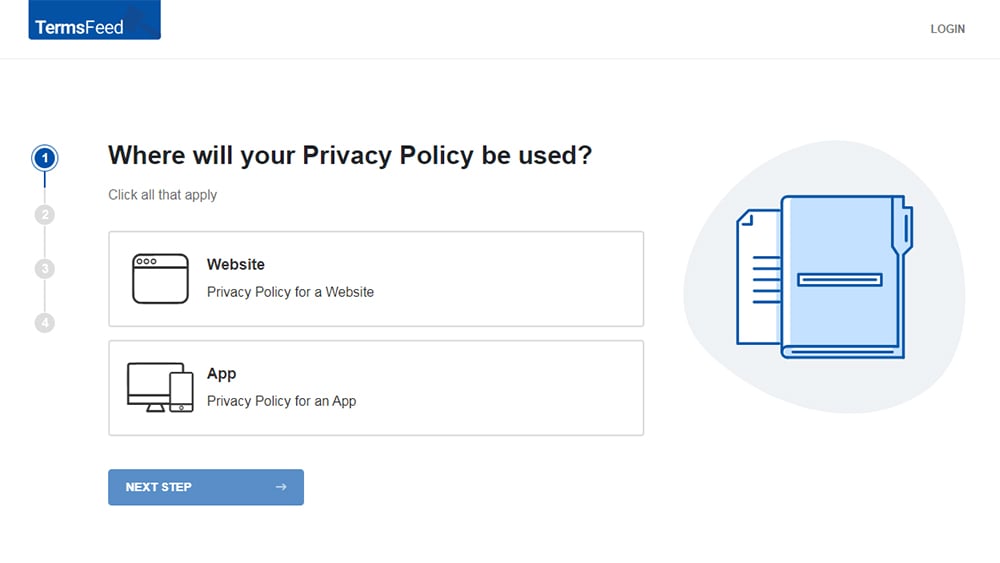

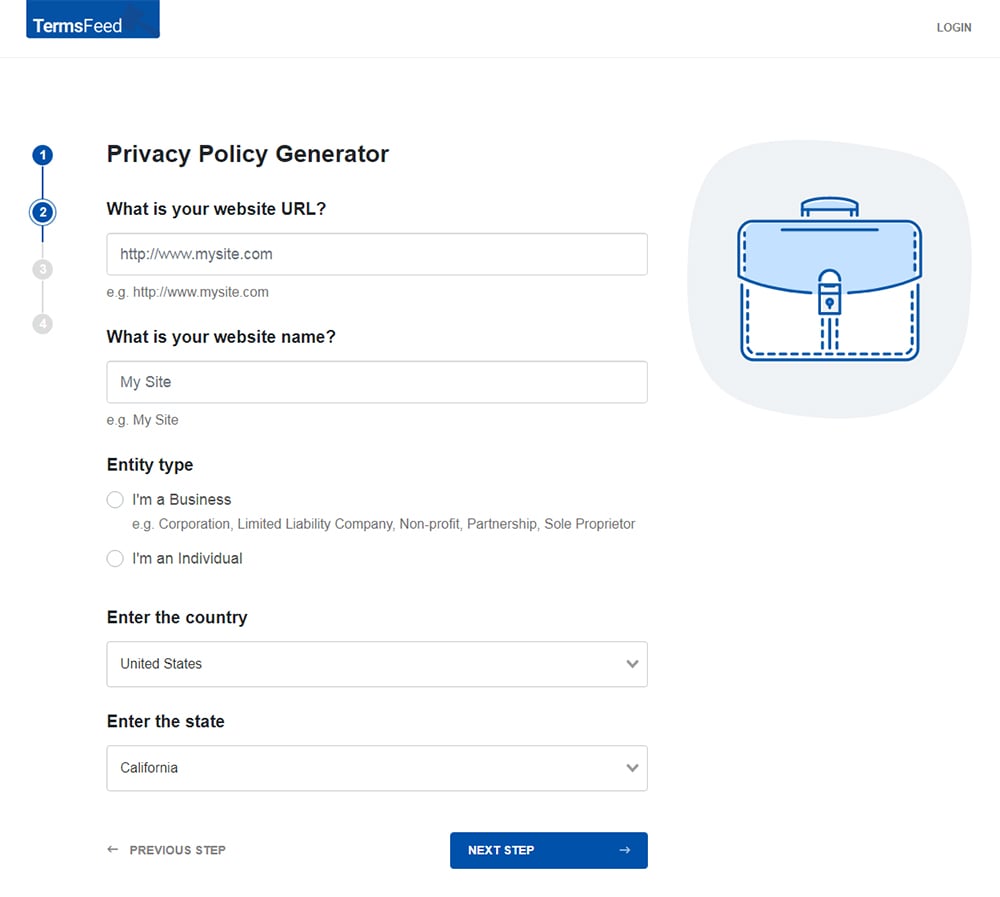

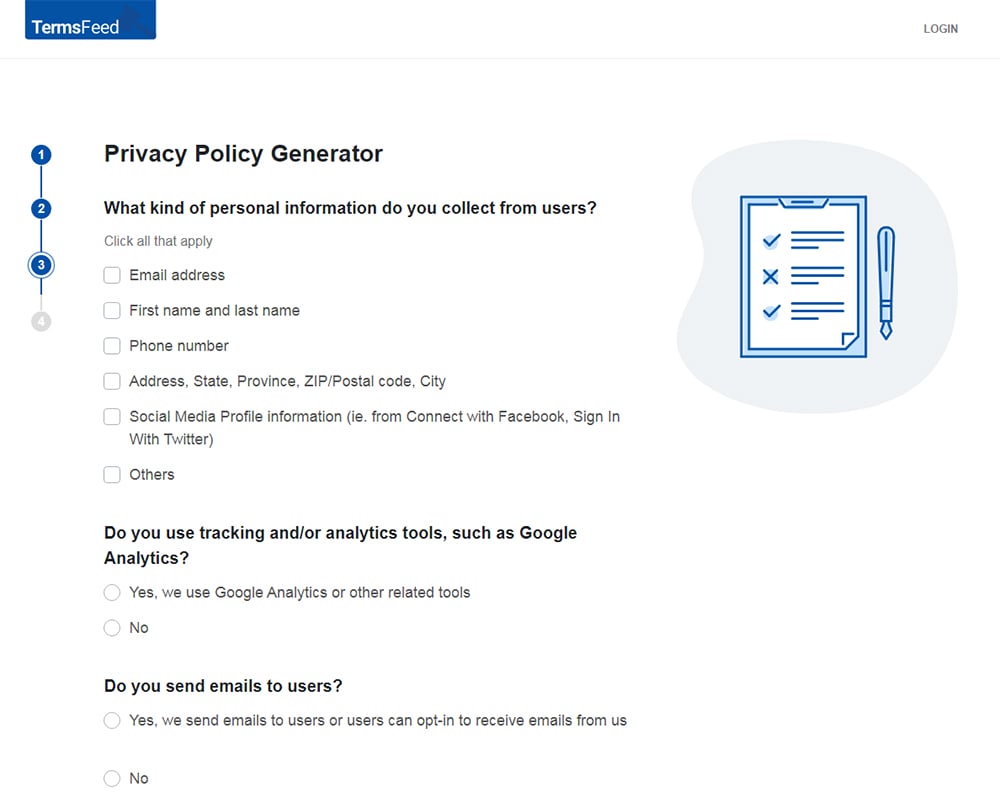

Our Privacy Policy Generator makes it easy to create a Privacy Policy for your business. Just follow these steps:

-

At Step 1, select the Website option or App option or both.

-

Answer some questions about your website or app.

-

Answer some questions about your business.

-

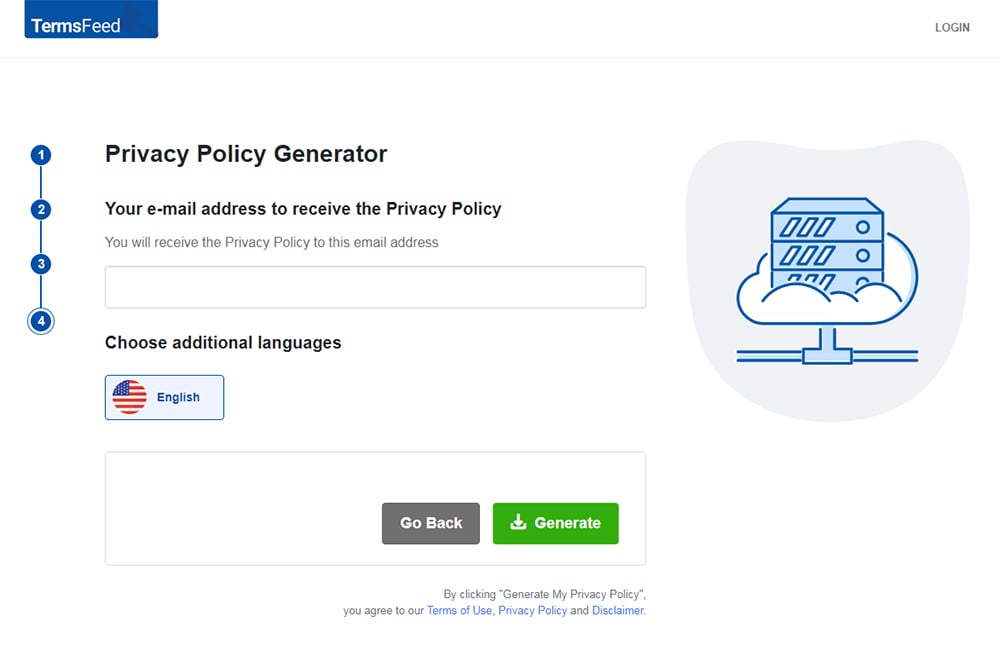

Enter the email address where you'd like the Privacy Policy delivered and click "Generate."

You'll be able to instantly access and download your new Privacy Policy.

- 1. Australia

- 1.1. Australia Main Privacy Laws and Application

- 1.2. Australia Definition of Personal Information

- 1.3. Australia Targeted Advertising Privacy Requirements

- 1.4. Australia Privacy Consent Requirements

- 1.5. Australia Privacy Policy Requirements

- 2. Argentina

- 2.1. Argentina Main Privacy Laws and Application

- 2.2. Argentina Definition of Personal Information

- 2.3. Argentina Targeted Advertising Requirements

- 2.4. Argentina Privacy Consent Requirements

- 2.5. Argentina Privacy Policy Requirements

- 3. Brazil

- 3.1. Brazil Main Privacy Laws and Application

- 3.2. Brazil Definition of Personal Information

- 3.3. Brazil Targeted Advertising Requirements

- 3.4. Brazil Privacy Consent Requirements

- 3.5. Brazil Privacy Policy Requirements

- 4. Canada

- 4.1. Canada Main Privacy Laws and Application

- 4.2. Canada Definition of Personal Information

- 4.3. Canada Targeted Advertising Requirements

- 4.4. Canada Privacy Consent Requirements

- 4.5. Canada Privacy Policy Requirements

- 5. China

- 5.1. China Main Privacy Laws

- 5.2. China Definition of Personal Information

- 5.3. China Targeted Advertising Requirements

- 5.4. China Privacy Consent Requirements

- 5.5. China Privacy Policy Requirements

- 6. European Union (EU)

- 6.1. European Union (EU) Main Privacy Laws and Application

- 6.2. European Union (EU) Definition of Personal Information

- 6.3. European Union (EU) Targeted Advertising Requirements

- 6.4. European Union (EU) Privacy Consent Requirements

- 6.5. European Union (EU) Privacy Policy Requirements

- 7. India

- 7.1. India Main Privacy Laws and Application

- 7.2. India Definition of Personal Information

- 7.3. India Targeted Advertising Requirements

- 7.4. India Privacy Consent Requirements

- 7.5. India Privacy Policy Requirements

- 8. Japan

- 8.1. Japan Main Privacy Laws and Application

- 8.2. Japan Definition of Personal Information

- 8.3. Japan Targeted Advertising Requirements

- 8.4. Japan Privacy Consent Requirements

- 8.5. Japan Privacy Policy Requirements

- 9. New Zealand

- 10. Nigeria

- 10.1. Nigeria Main Privacy Laws and Application

- 10.2. Nigeria Definition of Personal Information

- 10.3. Nigeria Privacy Consent Requirements

- 10.4. Nigeria Targeted Advertising Requirements

- 10.5. Nigeria Privacy Policy Requirements

- 11. South Africa

- 11.1. South Africa Main Privacy Laws

- 11.2. South Africa Definition of Personal Information

- 11.3. South Africa Privacy Consent Requirements

- 11.4. South Africa Privacy Policy Requirements

- 12. Sweden

- 13. United Kingdom (UK)

- 13.1. United Kingdom (UK) Main Privacy Laws and Application

- 13.2. United Kingdom (UK) Definition of Personal Information

- 13.3. United Kingdom (UK) Targeted Advertising Requirements

- 13.4. United Kingdom (UK) Privacy Consent Requirements

- 13.5. United Kingdom (UK) Privacy Policy Requirements

- 14. United States (Federal Laws)

- 14.1. United States (US) Main Privacy Laws and Application

- 14.2. United States (US) Definition of Personal Information

- 14.3. United States (US) Privacy Consent Requirements

- 14.4. United States (US) Targeted Advertising Requirements

- 14.5. United States (US) Privacy Policy Requirements

- 15. United States (State Laws)

- 16. United States (California)

- 16.1. California Main Privacy Laws

- 16.2. California Definition of Personal Information

- 16.3. California Targeted Advertising Requirements

- 16.4. California Privacy Consent Requirements

- 16.5. California Privacy Policy Requirements

Australia

Australia Main Privacy Laws and Application

Australia's main privacy laws are:

- The Privacy Act 1988

- The Spam Act 2003 (available here)

The Privacy Act sets out the "Australian Privacy Principles" (APPs). Only "APP Entities" are required to comply with the Privacy Act. APP Entities include:

- Government agencies

- Australian businesses with annual turnovers in excess of 3 million AUD

-

Any Australian business with an annual turnover below 3 million AUD if:

- It trades in personal information, or

- It provides healthcare services

The Spam Act applies to any business sending commercial emails with an "Australian link." A commercial email has an Australian link if:

- The email was sent from Australia, or

- It would be reasonable to expect that the email would be opened in Australia

Australia Definition of Personal Information

The Privacy Act defines "personal information" as:

"Information or an opinion about an identified individual, or an individual who is reasonably identifiable"

Personal information is also defined in another Australian Telecommunications (Interceptions and Access) Act 1979 (available here). It includes account information for phone and internet services and metadata about communications.

Australia Targeted Advertising Privacy Requirements

Australian law does not place strict rules on targeted advertising.

The Privacy Act doesn't specifically refer to cookies as a type of personal information, and consent is not required for setting cookies.

The Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) states that cookies revealing "general information about your interests and the websites you've visited" would not constitute personal information or fall under the scope of the Privacy Act.

Australia Privacy Consent Requirements

Australian law recognizes express and implied consent.

Express consent is not defined in the Privacy Act or the Spam Act. The OAIC defines express consent as being given "openly and obviously, either verbally or in writing."

Implied consent can arise when:

- A person has a pre-existing relationship with a business

- A person has published their contact details online without specifying that they do not wish to be contacted

Australia Privacy Policy Requirements

The Privacy Act requires every APP Entity to publish a Privacy Policy detailing:

- The kinds of personal information it collects and holds

- How it collects personal information

- How it stores personal information

- The purposes for which it collects, holds, uses, and discloses personal information

- How an individual may access or seek correction of their personal information

- How an individual may complain that it a breach of the Privacy Act

- Whether it is likely to disclose personal information to overseas recipients, and in which country

Argentina

Argentina Main Privacy Laws and Application

The main privacy law in Argentina is the Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA) (English version available here).

Much like EU privacy law, the PDPA applies to anyone processing personal information, regardless of the size of a business or its sector.

The law does not specifically state that it applies to businesses based outside of Argentina, but it does apply to all processing of personal information that takes place in Argentina.

Argentina Definition of Personal Information

The official English translation of the PDPA defines "personal data" as:

"Information of any kind referred to certain or ascertainable physical persons or legal entities."

Argentina Targeted Advertising Requirements

There are no specific rules related to cookies or targeted advertising in Argentine law.

Argentina Privacy Consent Requirements

Express consent is required for all "treatment" of personal information, and it must be "given in writing, or through other similar means," unless the personal information is:

- Publicly available

- Collected under state powers

-

Part of a list consisting of:

- Name

- National identity number

- Tax or social security identification

- Occupation

- Date of birth

- Address

- Phone number

- Necessary for the fulfillment of a contract

The PDPA doesn't make reference to implied consent.

Argentina Privacy Policy Requirements

The PDPA does not explicitly require businesses to publish a Privacy Policy. However, businesses must reveal the following information on request:

- The purpose for processing the personal information, and the identities of the "addressees" (recipients)

- Whether the business holds the individual's personal information, and who is responsible for it

- Whether the individual is required to provide personal information (particularly sensitive personal information) or whether they can refuse

- The consequences of providing or refusing to provide the personal information

- Information about the individual's rights to access, rectification, and suppression of personal information

Brazil

Brazil Main Privacy Laws and Application

There are two main privacy laws in Brazil:

- The Civil Rights Framework for the Internet (known as the "Marco Civil") (English version available here)

- The Brazilian General Data Protection Law (LGPD), which should take effect on August 16 2020

The LGPD applies to:

- All processing of personal information that takes place in Brazil

- Any processing of personal information that takes place for the purposes of offering goods or services to people in Brazil

- The processing of personal information that was collected in Brazil

This means that the LGPD affects businesses based outside of Brazil if they offer goods and services to, or collect personal information from, people in Brazil.

The law applies to everyone who processes personal information, and uses the terms "controller" and "processor" in the same way as the GDPR.

Brazil Definition of Personal Information

The LGPD defines "personal data" as:

"Information regarding an identified or identifiable natural person."

Bear in mind that this is a recently-drafted law that takes inspiration from the GDPR. As such, this definition is likely to be interpreted broadly, and will encompass many types of directly and indirectly identifying types of information.

Brazil Targeted Advertising Requirements

The LGPD does not specifically mention cookies or online identifiers. However, given the clear influence of the GDPR, it is possible that the definition of "personal information" will be interpreted to include data such as this.

Brazil Privacy Consent Requirements

The LGPD defines "consent" as:

"Free, informed and unambiguous manifestation whereby the data subject agrees to her/his processing of personal data for a given purpose."

This is a similar definition to that found in the GDPR.

The LGPD does not recognize implied consent, but like the GDPR it does recognize "legitimate interests" as an alternative lawful basis for processing personal information.

Consent must be given in writing or via some other recorded means.

Brazil Privacy Policy Requirements

The LGPD requires data controllers to provide transparent information, particularly when requesting consent. The following information must be provided:

- The purposes of processing the personal information

- The means and duration of processing

- The identity of the data controller

- Contact information for the data controller

- Whether the personal information will be shared, and for what purposes

- The responsibilities of the data controllers and processors that will process the personal information

- Information about the individual's rights over their personal information

Canada

Canada Main Privacy Laws and Application

Canada's main privacy laws are:

- Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA)

- Canada's Anti-Spam Legislation (CASL)

PIPEDA applies to all private sector organizations, regardless of size. Provincial laws take priority in certain provinces but these are substantially similar to PIPEDA.

Recently, decisions by Canada's courts and its Office of the Privacy Commissioner (OPC) have made it clear that any foreign business with a clear and substantial link to Canada is covered by PIPEDA.

CASL applies to anyone sending commercial email to Canadian consumers.

Canada Definition of Personal Information

PIPEDA defines personal information as:

"Information about an identifiable individual."

The OPC provides examples of personal information including ID numbers, income, and "intention to acquire goods or services."

Canada Targeted Advertising Requirements

The OPC considers technical information such as IP addresses, cookie data and device IDs to be personal information. This means that PIPEDA's requirements apply when using tracking cookies.

CASL covers the installation of certain "computer programs," including cookies.

CASL states that businesses require "express consent" for setting cookies. Somewhat confusingly, however, express consent for cookies can be assumed if "the person's conduct is such that it is reasonable to believe that they consent to the program's installation."

This threshold for "assumed express consent" can be met by providing transparent information about the use of cookies and a clear and accessible opt-out method.

Canada Privacy Consent Requirements

Canadian privacy law recognizes express and implied consent.

Under PIPEDA, express consent must be requested when collecting sensitive personal information, processing personal information in a way that would fall outside of the individual's reasonable expectations, or where there is a "meaningful residual risk of significant harm."

Implied consent is most relevant to CASL. An individual may give implied consent to receive direct email marketing if:

- They have an active business relationship with the sender (they have made a purchase in the past two years, or expressed interest in the business in the past six months)

- They have made their email address available in the public domain and they have interests relevant to the sender's business

Canada Privacy Policy Requirements

PIPEDA requires a company's Privacy Policy to contain the following information:

- Contact details of the company's Privacy Officer or other responsible person

- Information about the right to access personal information

- Disclosure of the personal information the company holds on the individual and its purposes for holding it

- Information about the company's other policies

- Disclosure of the what personal information the company shares with subsidiaries and other related organizations

China

China Main Privacy Laws

A patchwork of criminal, civil, and regulatory laws govern privacy in China. Some important examples include:

- The Cybersecurity Law of the People's Republic of China (CSL) (English version available here)

- The Draft Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL)

- The Personal Information Security Specification (English version available here)

- The Internet Email Services Regulations (Information in English available here)

- The Tort Law of the People's Republic of China (English version available here)

Sector-specific laws also exist in the areas of healthcare, finance, and telecommunications.

All businesses will be covered to some extent by one or more of these laws.

The Personal Information Security Specification applies to "controllers": people or businesses that make decisions about the processing of personal information.

The CSL regulates "risks and threats arising both within and without the mainland territory of the People's Republic of China" and therefore covers businesses based outside of China.

China Definition of Personal Information

The CSL defines "personal information" as:

"All kinds of information, recorded electronically or through other means, that taken alone or together with other information, is sufficient to identify a natural person's identity"

It provides the following non-exhaustive list of examples:

- Full names

- Birth dates

- National identification numbers

- Personal biometric information

- Addresses

- Telephone numbers

China Targeted Advertising Requirements

Chinese law does not specifically regulate the use of cookies or other targeted advertising tools.

In 2015, a Chinese appeal court heard a case brought against Baidu, the Chinese search engine. The claimant alleged that they had suffered emotional distress as a result of Baidu's use of tracking cookies.

Due to Baidu's adequate Privacy Policy and its provision of an opt-out mechanism, the court found in favor of Baidu.

China Privacy Consent Requirements

Consent is an important basis for the processing of personal information in the CSL and the Specification.

The Personal Information Security Specification defines express consent as "a freely given, specific, clear, and unequivocal indication of the wishes of the well-informed personal information subject." Express consent is required when collecting sensitive personal information.

China Privacy Policy Requirements

The Personal Information Security Specification requires controllers to publish a Privacy Policy containing the following information:

- Name and contact details of the controller

- The purposes for collecting personal information

- The categories of personal information collected for each purpose, the means of collecting personal information, the location and duration of storage, and the scope of the collection

- Information regarding the sharing of personal information including the purposes of sharing, the categories of personal information that are shared, the categories of recipients and their legal responsibilities

- The information security principles and security measures

- Information and individuals' rights to access, correct, erase personal information, and restrict automated decision-making

- The consequences of providing or refusing to provide personal information

- Information about making a complaint about the controller's privacy practices

European Union (EU)

European Union (EU) Main Privacy Laws and Application

The two main EU privacy laws are:

- The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)

- The ePrivacy Directive

These laws apply across the whole of the European Economic Area (EEA), which includes all EU Member States plus Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway.

Each EU Member State implements the laws slightly differently and has its own national privacy legislation. However, these national laws should not deviate significantly from the EU laws.

These laws apply across all sectors and to businesses of all sizes (although there are some exemptions to the GDPR for smaller businesses). Most of the GDPR's rules apply to "data controllers," which make decisions about how and why to process personal information.

EU privacy law applies explicitly to businesses based outside of the EU if they are offering goods or services to EU consumers or monitoring their behavior (including via the use of tracking cookies).

European Union (EU) Definition of Personal Information

The GDPR defines "personal data" as:

"any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person ('data subject'); an identifiable natural person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier [...]"

This is a very broad definition that can include anything from a person's name to information about their browsing history or device ID.

European Union (EU) Targeted Advertising Requirements

The use of cookies is strictly regulated in the EU. Controllers must request express consent for any cookies that are not strictly necessary for delivering the service or fulfilling a user's request.

This means a website operator must place a "cookie banner" on its website and not set advertising cookies until the user has given their consent. Refusing consent to advertising cookies must not result in the user being denied access to a website or service.

European Union (EU) Privacy Consent Requirements

"any freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous indication of the data subject's wishes by which he or she, by a statement or by a clear affirmative action, signifies agreement"

The GDPR only recognizes express consent, and the standard is very high. Consent must be easy to withdraw and refusing to consent must not result in any detriment to the individual.

While there is no concept of implied consent under EU law, the lawful basis of "legitimate interests" does allow certain forms of personal information processing, including direct marketing, to take place on an "opt-out" basis.

European Union (EU) Privacy Policy Requirements

A GDPR Privacy Policy must contain:

- The controller's contact details

- The types of personal information processed

- The purposes for processing personal information

- The categories of third party recipients of personal information

- The lawful bases for processing personal information

- The safeguards applied when transferring personal information out of the EU

- The duration of personal information storage

- An explanation of users' rights under the GDPR and how to access them

- Contact details for the relevant Data Protection Authority and an explanation of how to make a complaint

India

India Main Privacy Laws and Application

As of writing, India has not yet enacted a general privacy law but the Personal Data Protection Bill (PDPB) is in process of potentially getting approved.

The Information Technology Act 2000 (IT Act) (English version) is a cybersecurity law that covers certain aspects of privacy and data protection.

India Definition of Personal Information

The PDPB defines "personal data" as:

"Data about or relating to a natural person who is directly or indirectly identifiable, having regard to any characteristic, trait, attribute or any other feature of the identity of such natural person, or any combination of such features, or any combination of such features with any other information."

India Targeted Advertising Requirements

The PDPB doesn't make reference to cookies or targeted advertising. However, the broad definition of personal information is likely to be interpreted as including online identifiers such as cookies.

India Privacy Consent Requirements

Under the PDPB, consent must be:

- Free

- Informed

- Specific

- Clear

- Capable of being withdrawn

The Bill also specifically prohibits the denial of goods or services to an individual who refuses to give consent.

Consent under the PDPB is much like consent under the GDPR: implied consent is not recognized.

India Privacy Policy Requirements

A PDPB Privacy Policy must contain the following information:

- The categories of personal information collected and the means of collection

- The purposes for processing personal information

- The categories of personal information collected in exceptional circumstances

- An explanation of the rights people have over their personal information

- Information about how to file a complaint with a Data Protection Authority

- Contact details for the Indian Data Protection Authority and an explanation of how to make a complaint

The Indian Data Protection Authority may also specify new Privacy Policy requirements.

Japan

Japan Main Privacy Laws and Application

Japan's main privacy laws are:

- The Act on the Protection of Personal Information (APPI) (English version)

- The Act on Specified Commercial Transactions (ASCT) (available in English here)

- The Act on Regulation of the Transmission of Specified Electronic Mail (English version)

The APPI applies to all private businesses. Government entities and certain other journalistic and religious organizations are exempt.

Japan Definition of Personal Information

The APPI defines "personal information" as "information relating to a living individual." It divides personal information into two categories:

- A name, date of birth, or "other description" that could lead to the identification of an individual

- An individual identification code

Japan Targeted Advertising Requirements

Japanese law does not specifically mention targeted advertising. However, it is possible that cookies and other online identifiers could fall under the definition of personal information.

Because the transfer of personal information requires consent under the APPI, it is possible that this would apply to third-party cookies, meaning that cookie banners would be necessary for certain types of targeted advertising.

Japan Privacy Consent Requirements

The APPI doesn't define consent. Consent is required for the collection of sensitive personal information and for the transfer of personal information to third parties.

Under the ASCT, consent is required for marketing emails, unless they are sent alongside transactional emails.

Japan Privacy Policy Requirements

A basic Privacy Policy under the APPI must give notice of:

- The name of the company

- The company's purposes for processing personal information

- Individuals' rights over their personal information

New Zealand

New Zealand's Privacy Act 2020 has 13 principles that promote privacy. The principles are as follows:

- Only collect personal information that's necessary for a lawful purpose

- When possible, collect personal information direction from individuals themselves

- Disclose why you collect information, who you share it with, what choices users have, what happens if users refuse to share data

- Only collect personal information in a fair, lawful and unintrusive way

- Have resonable safeguards in place to protect the data

- Allow individuals to access their own data you have collected, with exceptions

- Upon request, correct an individual's personal information if inaccurate

- Make efforts to ensure personal information is accurate, up to date and complete

- Only keep the information for as long as you need it

- Only use the information for the purpose you collected it for

- Only disclose the information to third parties in specific instances

- Become familiar with overseas disclosure requirements

- Learn to use unique identifiers

A great way to satisfy some of these requirements is to have a Privacy Policy.

Nigeria

Nigeria Main Privacy Laws and Application

Nigeria's main privacy laws are:

- The National Information Technology Development Agency Act 2007 (English version)

- The Nigerian Data Protection Regulation 2019 (NDPR) (English version)

The Nigerian Data Protection Regulation applies to anyone processing the personal information of people in Nigeria, including businesses based outside of Nigeria.

Nigeria Definition of Personal Information

The NDPR defines "personal data" as:

"Any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person ('data subject'); an identifiable natural person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier."

This is virtually identical to the definition of personal information under the GDPR.

The definition is accompanied by an extensive list of examples, including:

- Photos

- MAC address

- IP address

These examples clearly show that this is intended as a very broad interpretation of personal information.

Nigeria Privacy Consent Requirements

The NDPR defines "consent" as:

"Any freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous indication of the data subject's wishes by which he or she, by a statement or by a clear affirmative action, signifies agreement to the processing of personal data relating to him or her."

This is virtually identical to the definition of consent under the GDPR. There is no concept of implied consent under the NDPR.

Nigeria Targeted Advertising Requirements

Cookies are mentioned specifically in the NDPR as a form of personal information, and a business must explain how it uses such technologies in its Privacy Policy.

Consent is not explicitly required for setting cookies, however it would appear to be the only appropriate lawful basis for doing so. Unlike the GDPR, the NDPR lacks a lawful basis of "legitimate interests."

Nigeria Privacy Policy Requirements

Under the NDPR, a Privacy Policy must contain:

- A description of what constitutes an individual's consent

- A description of the personal information collected

- The purposes for which personal information is collected

- A description of the technical methods used to collect and store personal information, including cookies, JSON web tokens, etc.

- A disclosure of any third-party access to personal information and an explanation of the purposes for any such access

- A summary of the NDPR's principles of personal information processing

- An explanation of the remedies available if the Privacy Policy is violated

- The time-frame for receiving such remedies

- Any relevant limitation clause, so long as it complies with the NDPR's principles of personal information processing

South Africa

South Africa Main Privacy Laws

There are two main privacy laws in South Africa:

- The Electronic Communications and Transactions Act 2002 (available here)

- The Protection of Personal Information Act (POPI Act)

The POPI Act looks set to be enforced from April 2020 after many years of delay (the law passed in 2013).

The POPI Act will apply to all South African businesses, and businesses based outside of South Africa that process personal information inside South Africa. There is an exception for foreign businesses that "forward personal information through South Africa."

South Africa Definition of Personal Information

The POPI Act defines "personal information" as:

"Any voluntary, specific and informed expression of will in terms of which permission is given for the processing of personal information."

South Africa Privacy Consent Requirements

The POPI Act defines consent as:

"A voluntary, specific and informed expression of will."

This is a form of express consent. The POPI Act does not recognize implied consent.

South Africa Privacy Policy Requirements

A POPI Act Privacy Policy must contain:

- The company's name and contact details

- The sources and nature of the personal information collected

- The purposes for collecting personal information

- What will happen if an individual fails to provide personal information

- Information about the rights of access and correction

Sweden

Sweden's Protective Security Act applies to both private and public organizations that engage in activities that are considered "security sensitive."

It comes with a number of requirements, including conducting a security analysis and implementing appropriate security measures.

Secure handling of data is at the heart of Sweden's law, which helps protect personal information from its citizens. Having a Privacy Policy is another layer of protection you can offer to your users here.

United Kingdom (UK)

United Kingdom (UK) Main Privacy Laws and Application

The main privacy laws in the UK are:

The DPA is the UK's implementation of the EU GDPR. Large sections of the Act refer to the GDPR and simply transpose the GDPR directly into the UK's national law. Other parts make specific exemptions and modifications that apply exclusively to the UK.

The PECRs are the UK's implementation of the EU ePrivacy Directive. They are substantially very similar to the ePrivacy Directive but, like the DPA, it applies specifically to the UK. The PECRs regulate online and telephone marketing.

The DPA and PECRs apply to all businesses processing the personal information of people in the UK. This includes businesses based outside of the UK if they are offering goods or services to UK consumers, or engaged in targeted marketing campaigns that involve UK consumers.

The UK also transposed the GDPR into its national law upon leaving the EU. There are no plans to amend or revoke the GDPR at this stage.

United Kingdom (UK) Definition of Personal Information

The DPA refers to the definition of personal information provided in the GDPR.

United Kingdom (UK) Targeted Advertising Requirements

The PECRs contain the same rules on targeted advertising as found in EU law.

United Kingdom (UK) Privacy Consent Requirements

The DPA contains the same consent requirements as the GDPR.

United Kingdom (UK) Privacy Policy Requirements

The DPA contains the same Privacy Policy requirements as the GDPR.

United States (Federal Laws)

United States (US) Main Privacy Laws and Application

Unlike most jurisdictions, the US does not have a general privacy law. Some important sector-specific federal privacy laws include:

- The Children's Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA), which applies to businesses collecting the personal information of children under 13

- The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), which applies to healthcare providers and insurers

- The Controlling the Assault of Non-Solicited Pornography And Marketing Act (CAN-SPAM), which covers unsolicited email marketing

United States (US) Definition of Personal Information

The main definition of personal information in US federal law comes from COPPA:

"Individually identifiable information about an individual collected online, including:

- a first and last name;

- a home or other physical address including street name and name of a city or town;

- an e-mail address;

- a telephone number;

- a Social Security number;

- any other identifier that the Commission determines permits the physical or online contacting of a specific individual; or

- information concerning the child or the parents of that child that the website collects online from the child and combines with an identifier described in this paragraph"

United States (US) Privacy Consent Requirements

COPPA requires businesses to earn express, verifiable parental consent from parents before processing the personal information of a child under 13.

HIPAA permits a covered entity to obtain consent for disclosing health information, but it does not actually require the entity to do so.

United States (US) Targeted Advertising Requirements

COPPA prohibits the use of tracking cookies where children under the age of 13 are concerned, unless the business has obtained verifiable parental consent.

United States (US) Privacy Policy Requirements

Under COPPA, a Privacy Policy must contain:

- The name, address, telephone number, and email address of all businesses collecting children's personal information through the company's websites (or one point of contact for all businesses)

- The types of personal information collected

- Disclosure of whether children can make their personal information publicly available through the company's website or service

- How the company shares personal information

- How the company uses personal information

- Information about parents' rights over their children's personal information and how parents can exercise those rights

United States (State Laws)

A few states have their own comprehensive privacy laws in place to protect its residents, and more are on the horizon to create such laws. While California continues to have the most privacy laws (discussed in the next section), here are some of the other key laws across the United States:

- Virginia's VCDPA

- Maryland's PIPA

- Colorado's Privacy Act

There are also state laws that address biometrics privacy issues and other aspects of privacy, without being as comprehensive as some of the others. These laws include the following:

- Texas: Capture or Use of Biometric Identifier Act (CUBI)

- Louisiana: Database Security Breach Notification Law

- New York: Stop Hacks and Improve Electronic Data Security Act (SHIELD)

- Washington: H.B. 1493

- Illinois: Biometric Information Privacy Act (BIPA)

- Oregon: Consumer Information Protection Act (OCIPA)

- Maryland: Personal Information Protection Act (PIPA)

United States (California)

California Main Privacy Laws

The State of California has several powerful privacy laws, including:

- California Online Privacy Protection Act (CalOPPA)

- California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA)

- California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA)

- California "Shine the Light" Law

- California "Online Eraser" Law

One or more of these laws will impact on any business whose website is accessible in California. This includes businesses based outside of the US.

For information about how these laws apply, see our article Sample California Privacy Policy Template.

California Definition of Personal Information

CalOPPA defines "personally identifiable information" as one of the following categories of identifier:

- First and last name

- Home or other address, including street name and name of a city or town

- Email address

- Telephone number

- Social security number

- Any other identifier that allows the contacting of a specific individual

- Information concerning a user that the website or online service collects online from the user and maintains in a personally identifiable form together with one of the identifiers above

The CCPA defines "personal information" as:

"Information that identifies, relates to, describes, is capable of being associated with, or could reasonably be linked, directly or indirectly, with a particular consumer or household."

This is arguably the broadest definition of personal information found in any privacy law in the world.

California Targeted Advertising Requirements

Under CalOPPA and the CCPA, a business must disclose its use of tracking cookies in its Privacy Policy.

Under the CCPA, certain uses of cookies may qualify as a "sale" of personal information. In this case, a business must offer consumers the right to opt-out.

California Privacy Consent Requirements

None of the four laws mentioned above requires a business to earn consent for the processing of personal information, with one exception.

Under the CCPA, a business must earn consent from a minor aged between 13-16 before they can sell the minor's personal information. If the minor is aged under 13, the business must earn parental consent.

Businesses must grant consumers over 16 the right to opt-out of the sale of their personal information.

California Privacy Policy Requirements

Under CalOPPA, a business must include the following information in its Privacy Policy:

- The categories of personal information collected via the company's website or app

- The categories of third parties to whom the company discloses personal information

- A description of any means by which a consumer may access or modify their personal information

- Notice of how the company will inform consumers of changes to its Privacy Policy

- The Privacy Policy's effective date

- A disclosure of how the company's website treats "Do Not Track" signals

- A disclosure regarding whether other parties may collect the user's personal information across other websites once they've left the company's website or app

California's "Shine the Light" and "Online Eraser" laws both require businesses to explain the consumer rights granted under these laws.

The CCPA's Privacy Policy requirements are more extensive.

For more information, see our article CCPA Privacy Policy Checklist.

Comprehensive compliance starts with a Privacy Policy.

Comply with the law with our agreements, policies, and consent banners. Everything is included.