If you're choosing to rely on legitimate interests as your lawful basis for processing personal data, it's important you can demonstrate that you've done some background work in determining that this is the right lawful basis for your purposes. This is called a Legitimate Interests Assessment.

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) doesn't provide doesn't provide a clear means by which you can carry out a Legitimate Interests Assessment. However, the UK's data authority, the Information Commissioner's Office (ICO), suggests a three-part test that should help you to consider whether you have a legitimate interest in processing your users' personal data.

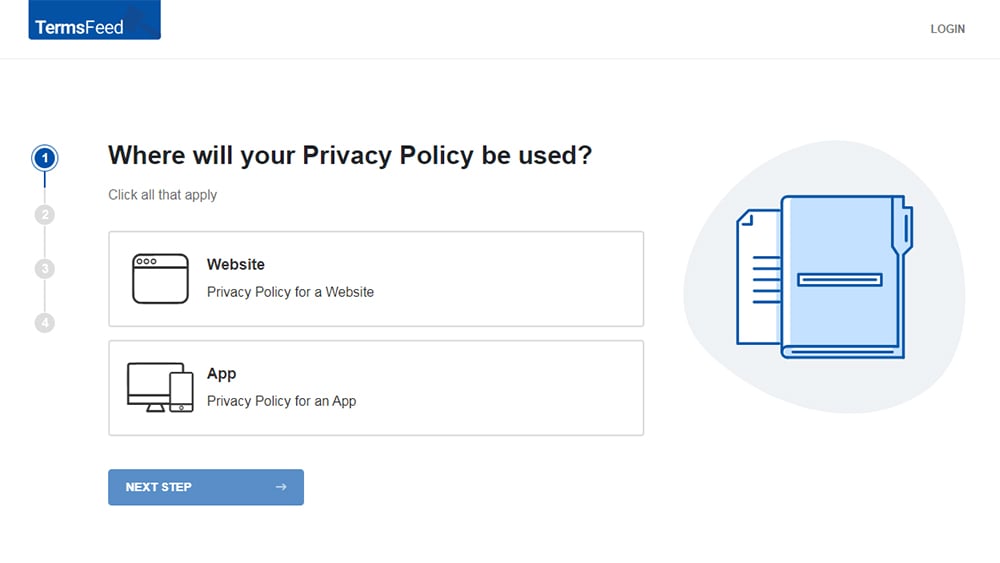

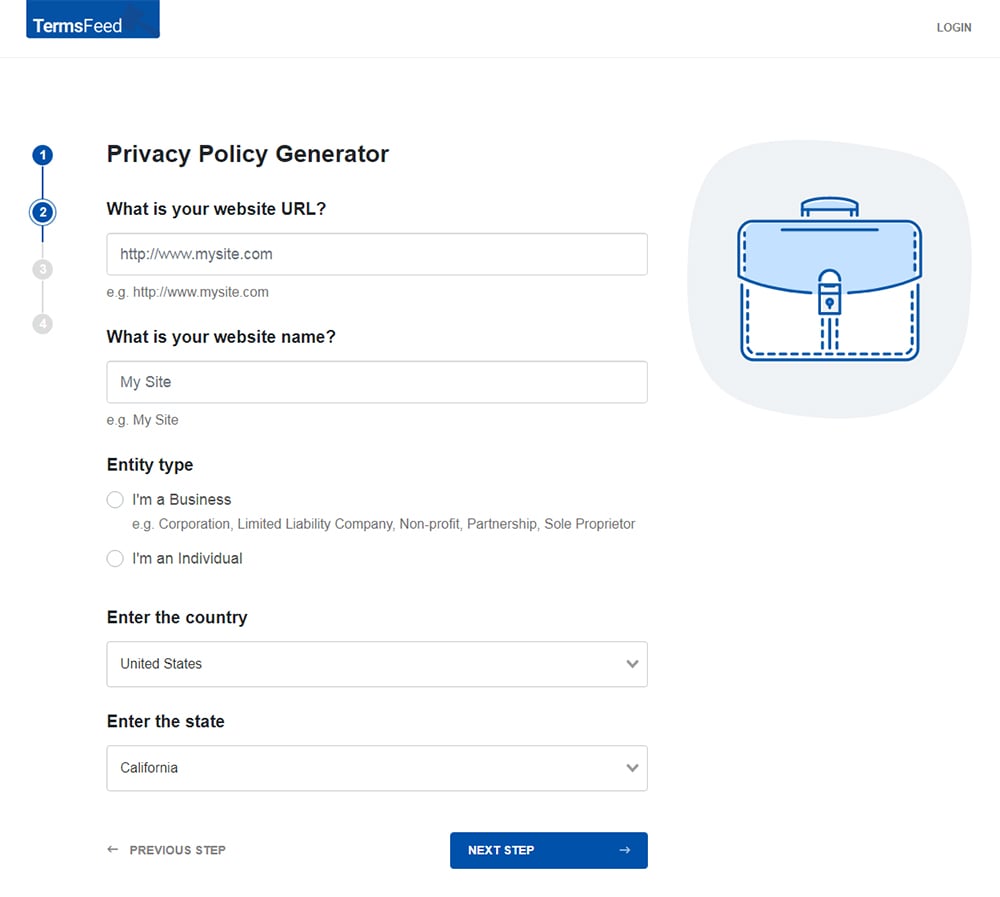

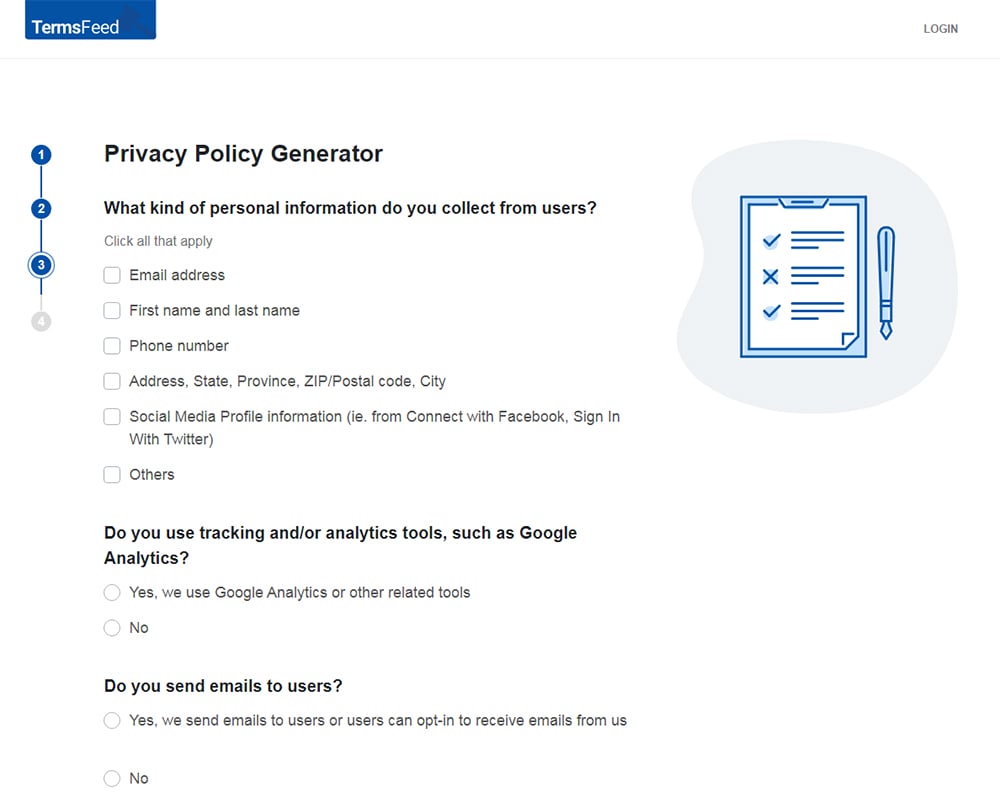

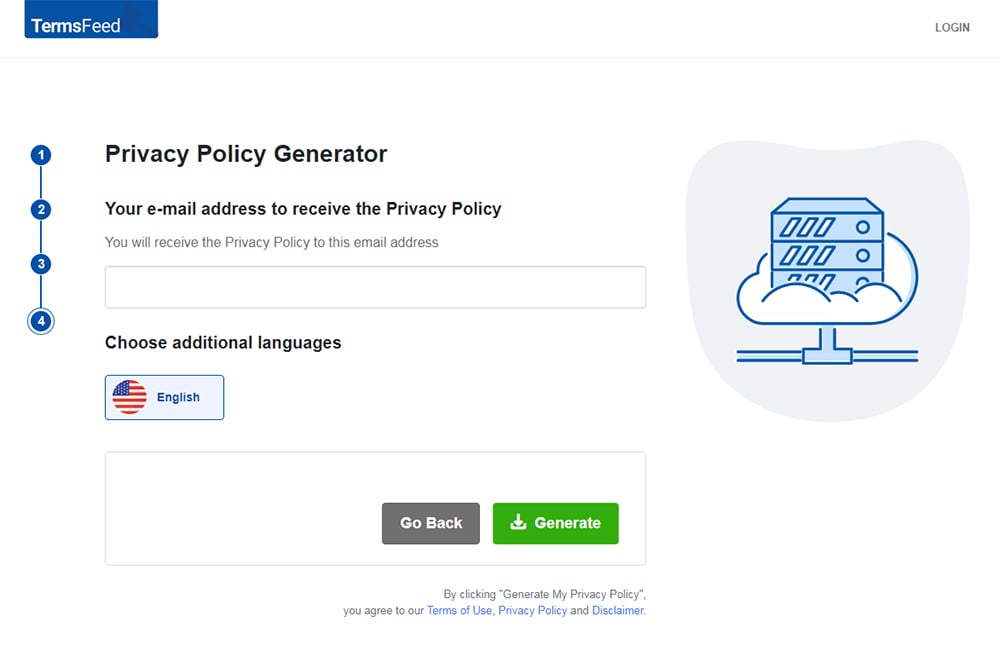

Our Privacy Policy Generator makes it easy to create a Privacy Policy for your business. Just follow these steps:

-

At Step 1, select the Website option or App option or both.

-

Answer some questions about your website or app.

-

Answer some questions about your business.

-

Enter the email address where you'd like the Privacy Policy delivered and click "Generate."

You'll be able to instantly access and download your new Privacy Policy.

- 1. Lawful Basis

- 2. Legitimate Interests Assessment

- 3. Part One - Purpose

- 3.1. Is it in Your Interests?

- 3.2. Is it Lawful?

- 3.3. Is it Ethical?

- 4. Part Two - Necessity

- 4.1. Is it Proportionate?

- 4.2. Are There Alternatives?

- 5. Part Three - Balance

- 5.1. Is it High-Risk?

- 5.2. What's the Impact?

- 6. Your Privacy Policy

- 7. Summary of Your Legitimate Interests Assessment

Lawful Basis

The GDPR exists to protect the "fundamental rights and freedoms" of EU citizens in relation to their personal data. One of the ways it does this is by requiring that any processing of personal data takes place on a "lawful basis."

This means that you can't just process someone's personal data for any arbitrary reason. You must have a legally valid reason for doing so.

And for most purposes, this means all processing of any personal data in the EU, for example:

- Collecting someone's name on your website

- Storing a mailing list

- Using certain cookies

- Taking payments on your website

Article 6 of the GDPR sets out the six lawful bases on which you can process personal data. You might have a person's consent to process their personal data. Or, you might need to do so if ordered to by a court. Or, processing their personal data might be in your legitimate interests.

Legitimate Interests Assessment

Let's take a look at Article 6 (1)(f) of the GDPR, where the term "legitimate interests" first appears. Processing is lawful if it:

"is necessary for the purposes of the legitimate interests pursued by the controller or by a third party, except where such interests are overridden by the interests or fundamental rights and freedoms of the data subject which require protection of personal data, in particular where the data subject is a child."

You can break this down into three key questions - a three-part test:

-

The purpose test: Are you processing personal data in pursuit of a legitimate interest?

- Is the processing in your interests?

- Is it legal?

- Is it ethical?

-

The necessity test: Do you need to this process personal data?

- Is the processing proportionate to achieving your aims?

- Are there any less intrusive alternatives?

-

The balancing test: Is your legitimate interest overridden by the rights of the person whose data you're processing?

- Is the processing high-risk?

- What will its likely impact be on your users?

There are countless scenarios where a Legitimate Interests Assessment might be necessary. For example:

- An HR department that runs checks on interview candidates

- An IT company that tracks visitors to a website for security reasons

- A bar that keeps a list of customers who are banned from its premises

We'll consider the scenario of a business that wants to rely on legitimate interests as its lawful basis for direct marketing.

You might have heard that the GDPR is very strict about consent. This is true. However, Recital 47 of the GDPR makes a statement that might surprise you:

"The processing of personal data for direct marketing purposes may be regarded as carried out for a legitimate interest."

Let's look at an example of how the three-part test might be carried out to allow direct marketing as a legitimate interest.

Part One - Purpose

The purpose test asks you to consider whether you are processing personal data in pursuit of a legitimate interest.

In the GDPR:

- "Legitimate" means in-line with the data processing principles of the GDPR, and what your users would reasonably expect.

- "Interests" is used in the sense of a benefit. If something is in your interests, you pursue it with an aim to benefit from it.

Because of the broad way in which legitimate interests are defined in the GDPR, it can be difficult to pin down a precise definition. The key thing to remember is that some types of data processing will represent a legitimate interest in some contexts, but not in others.

Is it in Your Interests?

Direct marketing involves advertising directly to people that you know something about because you think they might be interested in your products or services. It certainly might be in the interests of your business.

- It allows you to target a specific audience with your ads.

- You can easily measure the results of your campaigns.

- It's cost-effective.

You could also argue there are other benefits to third parties or wider society. For direct marketing, this is a little dubious - the main beneficiary will be your business.

So is direct marketing a legitimate interest? Potentially, if it's:

- Legal, and

- Carried out according to the principles of data processing

Is it Lawful?

Because of the annoyance that direct marketing can cause, there are a lot of rules and regulations around it. However, the GDPR only mentions direct marketing once.

There is another EU law that sometimes gets overlooked, which covers direct marketing. It's known as the ePrivacy Directive.

The ePrivacy Directive tells us that you need explicit consent for "unsolicited" direct marketing in form of:

- Automated phone calls

- Fax

- SMS

The GDPR doesn't replace the ePrivacy Directive. Its requirements for consent are just laid on top of it.

So, whereas previously, businesses tried to comply with the ePrivacy Directive by offering a "soft opt-in" to people who had no real relationship with their company, this is no longer legal under the GDPR.

So what about that statement in Recital 47 of the GDPR above that direct marketing might be in your legitimate interests?

The Information Commissioner's Office states that this might apply if a customer:

- Bought something from you recently;

- Gave you their contact details;

- Has been given a clear opportunity to opt out of marketing messages and declined to do so.

This is the "soft opt-in" exception that remains under the GDPR. It isn't appropriate if your lawful basis is consent, which must be achieved via a "hard opt-in" under the GDPR. But instead of relying on consent, you might argue that direct marketing under these conditions is in your legitimate interests.

Is it Ethical?

Data protection and privacy laws don't aim to suffocate businesses or deny them opportunities for growth. The leeway the GDPR provides isn't a loophole. If your company's direct marketing efforts are genuinely legitimate, you should be able to pursue them.

All data processing must adhere to the GDPR's six data processing principles. The most relevant in this context is the first one - "fairness, lawfulness and transparency." The key element of this principle here is fairness. Is it fair to use someone's contact details for marketing purposes?

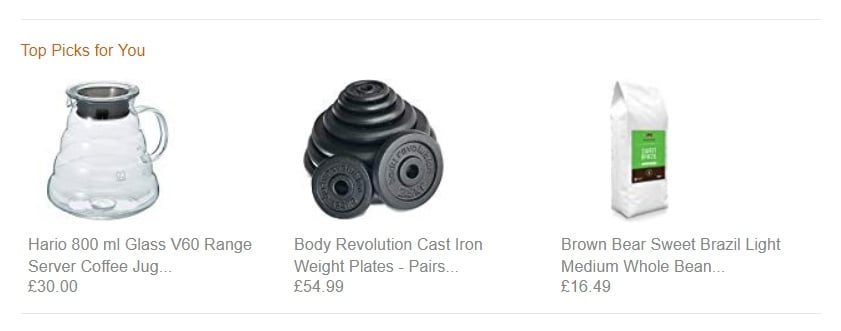

Here's an example of some direct marketing from Amazon, sent alongside an order confirmation:

A regular customer to Amazon is unlikely to object to receiving this type of direct marketing. But if they do, they are invited to opt out. This is a fair use of their personal data, and it's in Amazon's legitimate interests to market in this way.

Part Two - Necessity

The necessity test is designed to ensure that you're really sticking both to the letter and the spirit of the GDPR. Businesses can't just evade the GDPR's high standards of consent by claiming this or that is in their legitimate interests. They have to actually need to carry out the processing in question.

But don't panic - the word "necessity" can be interpreted somewhat broadly. We'll look at this again through the lens of direct marketing.

Is it Proportionate?

Your aims might be:

- To grow as a business

- To deepen your relationship with your existing customers

- To gauge the effectiveness of your advertising

These are all legitimate objectives. Direct marketing is one way of processing your users' personal data in pursuit of them. But do you need to do it this way?

The Charities Institute Ireland provides some guidance for its members on how to carry out a Legitimate Interests Assessment. It offers this interpretation of the necessity test:

"The processing would be necessary if there is no other way or if the alternative way of achieving the objective would be too onerous. Where however, there are several other alternatives to achieving the objective, then it is imperative that your charity chooses the least intrusive alternative."

In this context, direct marketing starts to seem like a necessary way of achieving aims such as the ones above.

Are There Alternatives?

There are other ways to grow your business through advertising than direct marketing, of course. Ads directed at the general public, sponsorship, and community engagement can be a viable part of your advertising strategy.

However, these methods don't serve to deepen your relationship with your existing customers as well as direct marketing does. This is something that direct marketing arguably does uniquely well.

The ICO asks you to consider the following question as part of the necessity test:

"Can you achieve the same purpose by processing less data, or by processing the data in another more obvious or less intrusive way?"

It is difficult to imagine a less intrusive but equally effective way to deepen your existing relationships with and generate further sales from your existing customers than direct marketing. The key is to do it in an unobtrusive way.

In the spirit of the necessity test, there are some ways that you might keep your direct marketing as unobtrusive as possible:

- Not bombarding your users - send direct marketing emails only occasionally.

- Considering whether some methods of direct marketing - such as SMS or automated calls - might be too intrusive.

- Keeping your correspondence subtle and polite, and not too pushy.

Part Three - Balance

Your legitimate interests must always be weighed against your users' "rights and freedoms," including their right not to have their personal data processed in ways that upset or bother them.

The final thing for you to consider in determining whether you can use legitimate interests as your lawful basis is whether you can demonstrate a balance between your interests and your users' rights.

Again, let's consider this using the example of direct marketing.

Is it High-Risk?

The first thing to consider when assessing your impact on your users' rights is whether you're processing sensitive personal data - known in the GDPR as "special category data." This is defined in Article 9 of the GDPR, as data:

"revealing racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs, or trade union membership, and the processing of genetic data, biometric data for the purpose of uniquely identifying a natural person, data concerning health or data concerning a natural person's sex life or sexual orientation [...]"

If you're processing special category data or any other "high-risk" personal data you'll need to consider very carefully whether your legitimate interests really override your users' rights not to have this data processed unnecessarily.

It would almost certainly not be appropriate to process special category data for the purposes of direct marketing without first obtaining your users' consent.

You also need to consider the way in which you're processing your users' personal data. You might be using new or untested technology. Recital 91 of the GDPR states that you need to conduct a "data protection impact assessment" if so.

What's the Impact?

Even if the personal data you're processing is not particularly sensitive (it might just be your customers' names and email addresses), your direct marketing campaign will still have an impact on them. You must consider whether this impact overrides your legitimate interests.

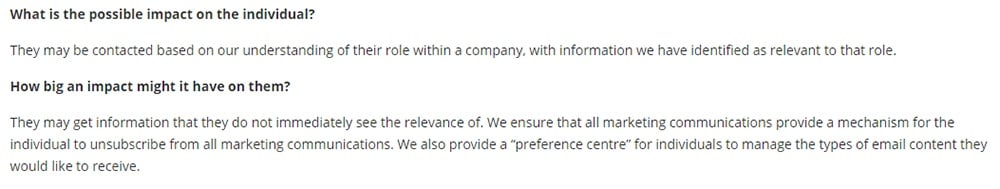

Consultancy firm Collier Pickard publishes its legitimate impact assessment as part of its Privacy Policy. Here's how it addresses the impact that its practices might have on its users:

What impact might your direct marketing campaign have? Well, if you keep it unobtrusive, transparent, and make the opt-out very clear, it's unlikely to have a significantly detrimental impact.

Legitimate interests can sometimes be a basis for risky types of data processing.

For example, a law firm might have a legitimate interest in storing highly sensitive information about clients. Their reasons to do so will usually be very compelling so they will be able to balance their interests against the risk to their clients.

Your Privacy Policy

Article 13 (d) of the GDPR says that if you're relying on legitimate interests as your lawful basis for processing data, you need to give your users information about "the legitimate interests pursued by [you] or by a third party."

This doesn't mean that you necessarily need to include your entire Legitimate Interests Assessment in your Privacy Policy - but it does mean that you should make reference to it.

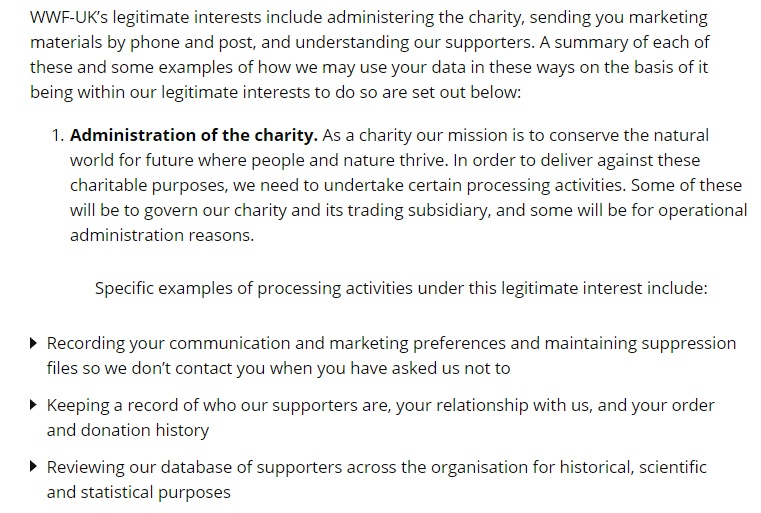

Environmental charity WWF gives a lot of detail about its legitimate interests in its Privacy Policy. It does so in clear and easily understood language. Here's an excerpt:

Summary of Your Legitimate Interests Assessment

Using legitimate interests as your lawful basis for processing personal data might sound easier than earning your users' consent. However, you need to do a lot of work before deciding it's the right lawful basis for your purposes.

- Think about your purpose for processing personal data:

- Why are you doing it?

- How will it benefit you?

- Will anyone else benefit?

- Is it legal to process personal data in this way?

- Is it ethical and in-line with the GDPR's six data processing principles?

- Think about the necessity of processing personal data in this way:

- Will it actually help you to your achieve your objectives?

- Is it a proportionate way of achieving them?

- Are there any alternative, less intrusive ways?

- Think about how you're balancing your interests and your users' rights:

- Are you processing special category or criminal conviction data?

- Are you processing data about children or vulnerable adults?

- Are you processing data in a new or untested way?

- Is your users' data safe?

- How might your data processing create an impact upon your users?

- Can you reduce this impact?

Comprehensive compliance starts with a Privacy Policy.

Comply with the law with our agreements, policies, and consent banners. Everything is included.