The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is comprised of 173 Recitals and 99 Articles.

Below you'll find a summary and brief explanation of each Recital of the GDPR.

The Recitals are important because they provide additional details and insight into the purpose and functions of the Articles.

*Please note that the Recital titles used here are not official

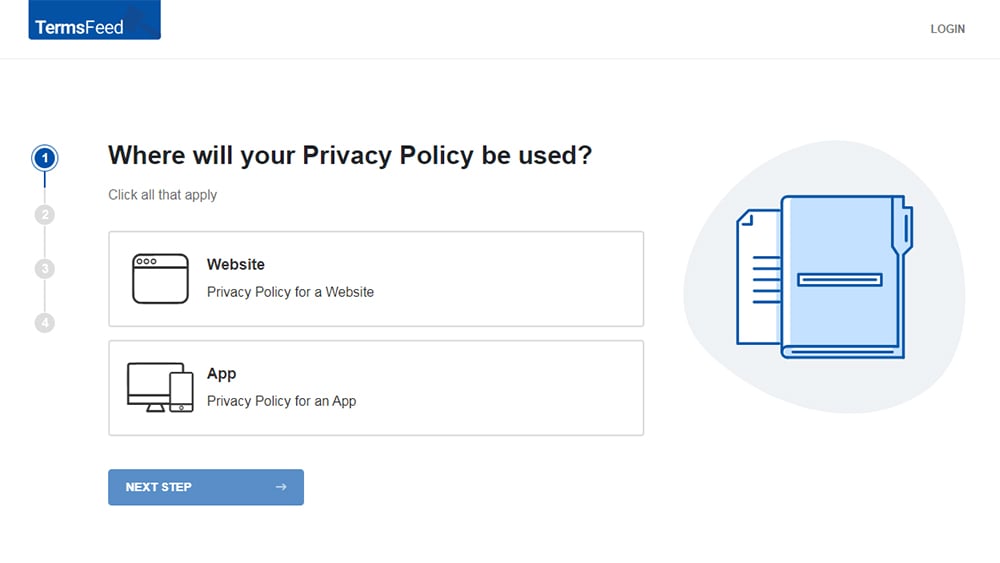

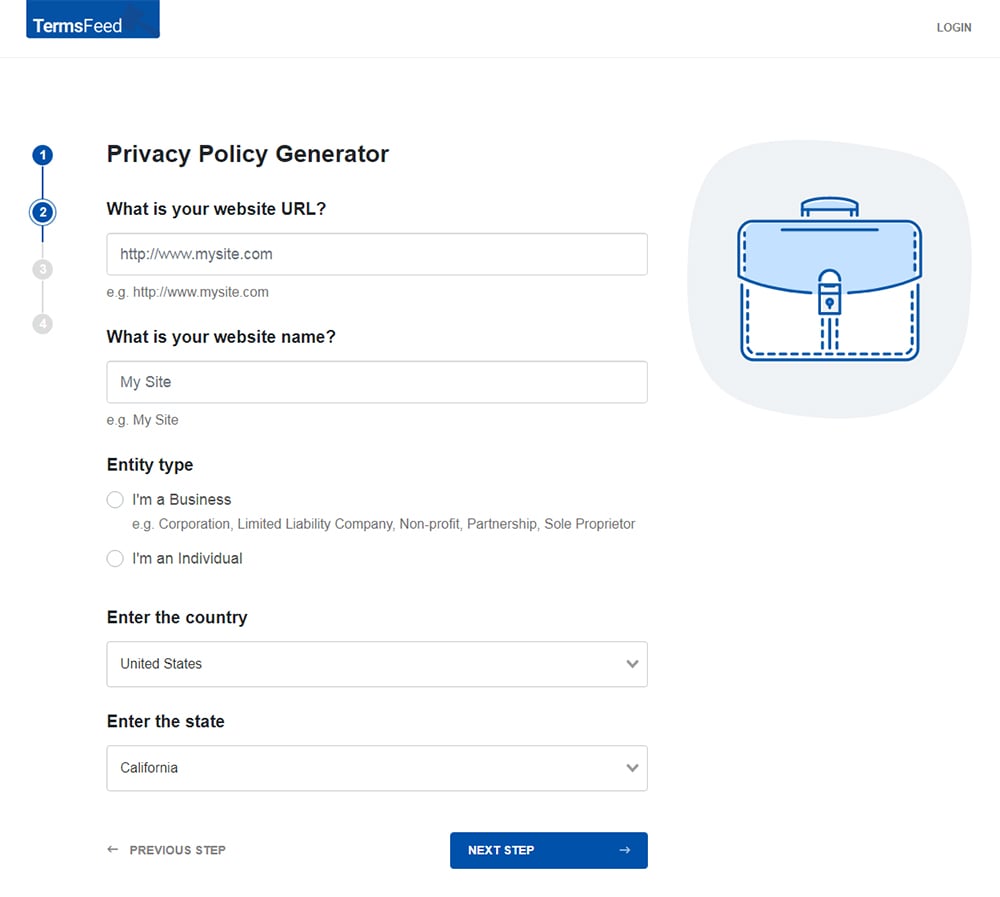

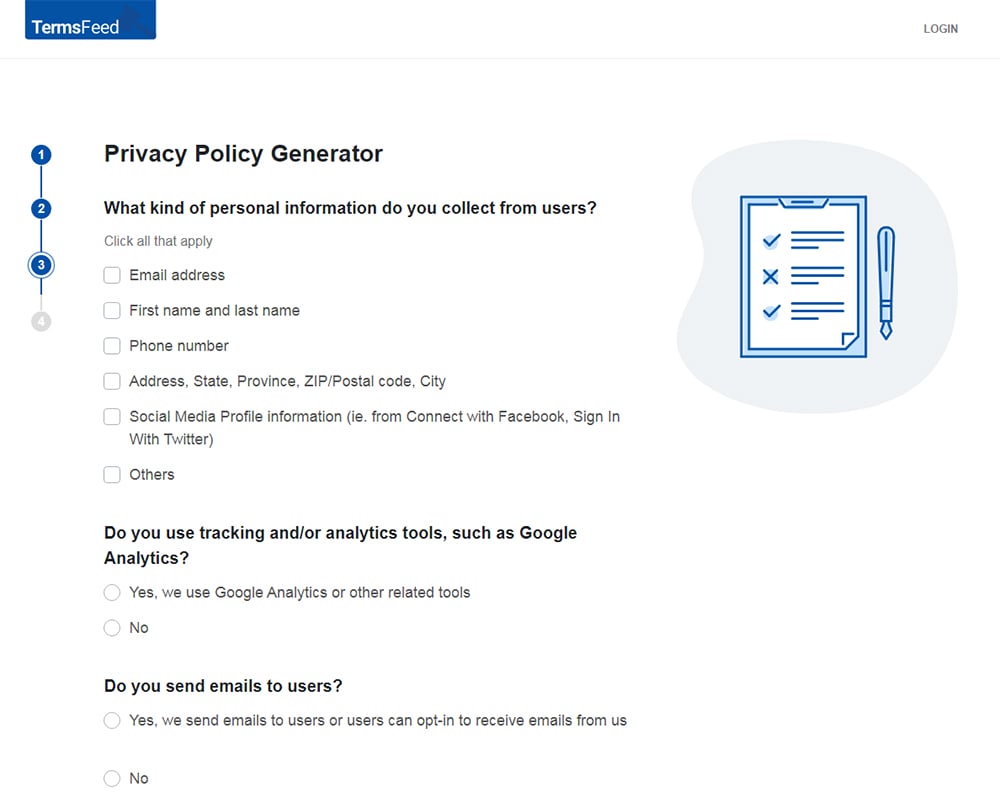

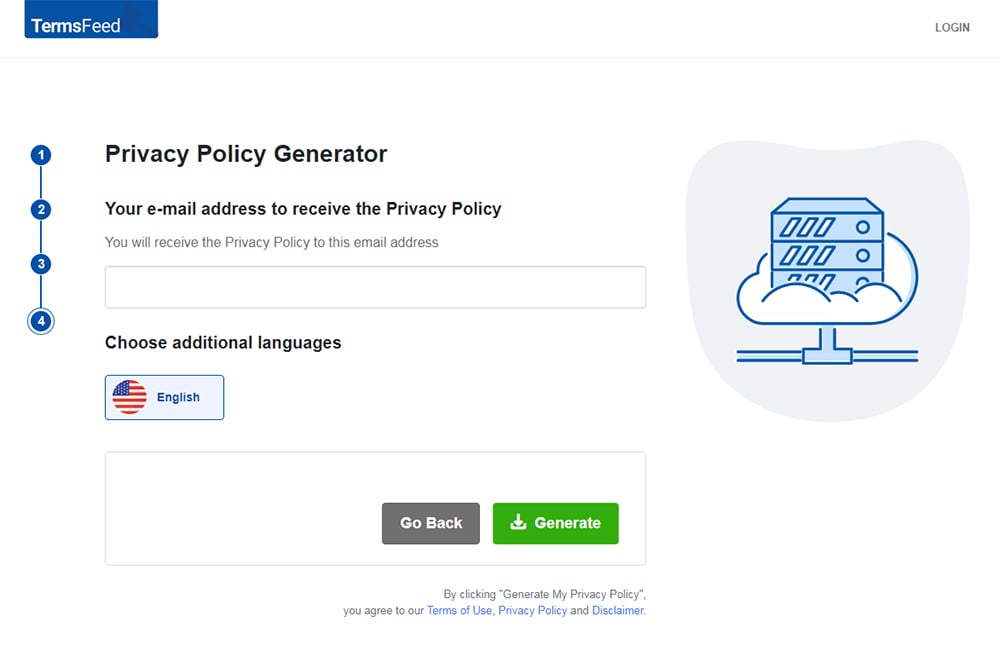

Our Privacy Policy Generator makes it easy to create a Privacy Policy for your business. Just follow these steps:

-

At Step 1, select the Website option or App option or both.

-

Answer some questions about your website or app.

-

Answer some questions about your business.

-

Enter the email address where you'd like the Privacy Policy delivered and click "Generate."

You'll be able to instantly access and download your new Privacy Policy.

- 1. Recital 1 - Fundamental Right to Data Protection*

- 2. Recital 2 - Aims of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)*

- 3. Recital 3 - Aims of the Data Protection Directive*

- 4. Recital 4 - Balancing of Rights*

- 5. Recital 5 - Requirement to Cooperate*

- 6. Recital 6 - Improvements in Technology*

- 7. Recital 7 - Why a New Framework*

- 8. Recital 8 - Integration into National Law*

- 9. Recital 9 - Data Protection Directive*

- 10. Recital 10 - Specifications in National Law*

- 11. Recital 11 - Effective Data Protection*

- 12. Recital 12 - Powers of the European Parliament and the Council*

- 13. Recital 13 - Necessity of the GDPR*

- 14. Recital 14 - Natural and Legal Persons*

- 15. Recital 15 - Unstructured Personal Data*

- 16. Recital 16 - National Security*

- 17. Recital 17 - Adaptation of Existing EU Law*

- 18. Recital 18 - Personal or Household Activity*

- 19. Recital 19 - Criminal Investigations*

- 20. Recital 20 - Judicial Activity*

- 21. Recital 21 - Intermediary Service Providers' Liability*

- 22. Recital 22 - Establishment in the EU*

- 23. Recital 23 - Offering Goods and Services in the EU*

- 24. Recital 24 - Monitoring Behavior in the EU*

- 25. Recital 25 - International Contexts*

- 26. Recital 26 - Anonymous Data*

- 27. Recital 27 - Deceased Individuals*

- 28. Recital 28 - Pseudonymization*

- 29. Recital 29 - Pseudonymization Within One Controller*

- 30. Recital 30 - Online Personal Data*

- 31. Recital 31 - Public Authorities*

- 32. Recital 32 - Conditions for Consent*

- 33. Recital 33 - Scientific Research*

- 34. Recital 34 - Genetic Data*

- 35. Recital 35 - Health Data*

- 36. Recital 36 - Main Establishment*

- 37. Recital 37 - Groups of Undertakings*

- 38. Recital 38 - Children's Personal Data*

- 39. Recital 39 - Data Processing Principles*

- 40. Recital 40 - Lawful Bases*

- 41. Recital 41 - Defining "Legal"*

- 42. Recital 42 - Consent*

- 43. Recital 43 - Freely Given Consent*

- 44. Recital 44 - Contract*

- 45. Recital 45 - Legal Obligation and Public Task*

- 46. Recital 46 - Vital Interests*

- 47. Recital 47 - Legitimate Interests*

- 48. Recital 48 - Sharing Personal Data as a Legitimate Interest*

- 49. Recital 49 - Ensuring Network Security as a Legitimate Interest*

- 50. Recital 50 - Further Processing*

- 51. Recital 51 - Special Category Data*

- 52. Recital 52 - Valid Reasons to Process Special Category Data*

- 53. Recital 53 - Special Category Health Data*

- 54. Recital 54 - Public Health*

- 55. Recital 55 - Religious Communities*

- 56. Recital 56 - Electoral Data*

- 57. Recital 57 - Identification*

- 58. Recital 58 - Transparency and Your Privacy Policy*

- 59. Recital 59 - Facilitating Data Rights*

- 60. Recital 60 - Providing Information*

- 61. Recital 61 - When to Provide Information*

- 62. Recital 62 - No Requirement to Provide Information*

- 63. Recital 63 - Access Requests*

- 64. Recital 64 - ID Requirements*

- 65. Recital 65 - Rectification and Erasure Requests*

- 66. Recital 66 - Erasing a Person's Online Presence*

- 67. Recital 67 - Restriction Requests*

- 68. Recital 68 - Portability Requests*

- 69. Recital 69 - Objection to Processing*

- 70. Recital 70 - Objection to Direct Marketing*

- 71. Recital 71 - Automated Decision-Making*

- 72. Recital 72 - Guidance for Profiling*

- 73. Recital 73 - Suspension of Data Rights*

- 74. Recital 74 - Controllers' Liability*

- 75. Recital 75 - Risks*

- 76. Recital 76 - Assessment of Risk*

- 77. Recital 77 - Guidance on Assessing Risk*

- 78. Recital 78 - Technical Measures*

- 79. Recital 79 - Allocating Responsibilities*

- 80. Recital 80 - Nominating a Representative*

- 81. Recital 81 - Data Processors*

- 82. Recital 82 - Keeping Records*

- 83. Recital 83 - Ensuring Security*

- 84. Recital 84 - Data Protection Impact Assessment*

- 85. Recital 85 - Data Breach Notification*

- 86. Recital 86 - Direct Notification to Users*

- 87. Recital 87 - Prompt Notification of Data Breaches*

- 88. Recital 88 - Rules About Data Breach Notification*

- 89. Recital 89 - Changes to Reporting Requirements*

- 90. Recital 90 - Mandatory Data Protection Impact Assessments*

- 91. Recital 91 - Circumstances Requiring an Impact Assessment*

- 92. Recital 92 - Large-Scale Data Protection Impact Assessment*

- 93. Recital 93 - State-Regulated Data Protection Impact Assessments*

- 94. Recital 94 - Consulting a Supervisory Authority*

- 95. Recital 95 - Assistance From Your Data Processor*

- 96. Recital 96 - Lawmaking and the Supervisory Authority*

- 97. Recital 97 - Data Protection Officer*

- 98. Recital 98 - Codes of Conduct*

- 99. Recital 99 - Consultation for Codes of Conduct*

- 100. Recital 100 - Certification Schemes*

- 101. Recital 101 - International Data Transfers*

- 102. Recital 102 - International Data Transfer Agreements*

- 103. Recital 103 - Third Country Adequacy Decisions*

- 104. Recital 104 - Adequacy Decision Conditions*

- 105. Recital 105 - Third Countries and International Agreements*

- 106. Recital 106 - Reviews of Third Countries' Data Protection*

- 107. Recital 107 - Amendment of Adequacy Decisions*

- 108. Recital 108 - Data Transfer Safeguards*

- 109. Recital 109 - Standard Data Protection Clauses*

- 110. Recital 110 - Binding Corporate Rules*

- 111. Recital 111 - Third-Country Transfer Exceptions*

- 112. Recital 112 - Third-Country Transfers and the Public Interest*

- 113. Recital 113 - Occasional and Small-Scale Data Transfers*

- 114. Recital 114 - Data Rights and Third-Country Transfers*

- 115. Recital 115 - Laws of Third Countries that Contradict the GDPR*

- 116. Recital 116 - Cooperation Between Supervisory Authorities*

- 117. Recital 117 - Establishing Supervisory Authorities*

- 118. Recital 118 - Monitoring Supervisory Authorities*

- 119. Recital 119 - Multiple Supervisory Authorities*

- 120. Recital 120 - Providing Resources for Supervisory Authorities*

- 121. Recital 121 - Membership of Supervisory Authorities*

- 122. Recital 122 - Responsibilities of Supervisory Authorities*

- 123. Recital 123 - Freedom of Cooperation for Supervisory Authorities*

- 124. Recital 124 - Lead Supervisory Authority*

- 125. Recital 125 - Powers of the Lead Supervisory Authority*

- 126. Recital 126 - Joint Decisions About Complaints*

- 127. Recital 127 - The "One-Stop-Shop" Mechanism*

- 128. Recital 128 - The "One-Stop-Shop" Mechanism and Public Bodies*

- 129. Recital 129 - Tasks of Supervisory Authorities*

- 130. Recital 130 - Complaints Lodged with Non-Lead Supervisory Authorities*

- 131. Recital 131 - Resolution Through Settlement*

- 132. Recital 132 - Raising Awareness*

- 133. Recital 133 - Mutual Assistance*

- 134. Recital 134 - Supervisory Authority Joint Operations*

- 135. Recital 135 - Consistency Mechanism*

- 136. Recital 136 - European Data Protection Board Decisions*

- 137. Recital 137 - Provisional Measures*

- 138. Recital 138 - Urgent Situations Across Borders*

- 139. Recital 139 - European Data Protection Board*

- 140. Recital 140 - Secretariat of the European Data Protection Board*

- 141. Recital 141 - Lodging a Complaint*

- 142. Recital 142 - Support by a Not-for-Profit*

- 143. Recital 143 - Judicial Review*

- 144. Recital 144 - Consolidation of Proceedings*

- 145. Recital 145 - Choice of Jurisdiction*

- 146. Recital 146 - Liability*

- 147. Recital 147 - Recast Brussels Regulation*

- 148. Recital 148 - Reprimands and Fines*

- 149. Recital 149 - Fines Issued by National Courts*

- 150. Recital 150 - Supervisory Authorities' Power to Issue Fines*

- 151. Recital 151 - Fines in Denmark and Estonia*

- 152. Recital 152 - Member States' Systems for Fines*

- 153. Recital 153 - Freedom of Expression*

- 154. Recital 154 - Public Documents*

- 155. Recital 155 - Employment*

- 156. Recital 156 - Archiving, Research, and Statistics*

- 157. Recital 157 - Scientific Research*

- 158. Recital 158 - Archiving*

- 159. Recital 159 - Definition of Scientific Research*

- 160. Recital 160 - Historical Research*

- 161. Recital 161 - Clinical Trials*

- 162. Recital 162 - Statistics*

- 163. Recital 163- European and National Statistics*

- 164. Recital 164 - Professional Secrecy*

- 165. Recital 165 - Churches*

- 166. Recital 166 - Delegated Acts*

- 167. Recital 167 - Implementing Powers*

- 168. Recital 168 - Use of the Examination Procedure*

- 169. Recital 169 - Immediate Adoption of Implementing Acts*

- 170. Recital 170 - Subsidiarity and Proportionality*

- 171. Recital 171 - Data Protection Directive*

- 172. Recital 172 - Consultation with the European Data Protection Supervisor*

- 173. Recital 173 - Relationship to the ePrivacy Directive*

Recital 1 - Fundamental Right to Data Protection*

Data protection is a fundamental right. Citizens of EU Member States owe this right, in part, to the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU and the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU.

Recital 2 - Aims of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)*

No matter where they are from, people have a right to protection of their personal data. Any rules around data processing should respect this right. The GDPR aims to:

- Advance economic and social progress;

- Bring EU economies closer together;

- Improve people's wellbeing.

Recital 3 - Aims of the Data Protection Directive*

The Data Protection Directive (an older EU law which the GDPR replaces) aims to:

- Equalize people's personal data rights across all EU Member States;

- Allow for the free flow of data across the EU.

Recital 4 - Balancing of Rights*

Data should be processed in a way that serves the public good. However, personal data rights have to be weighed against other rights. In setting out the rights people have over their personal data, the GDPR has to balance these against all of their other fundamental rights.

Recital 5 - Requirement to Cooperate*

A large amount of personal data is now flowing between EU Member States. EU law is asking those Member States to cooperate and carry out duties on behalf of one another.

Recital 6 - Improvements in Technology*

Technological improvements and globalization have brought about a huge increase in the amount of personal data being shared. Businesses and public bodies processing personal data on a large scale. This increase in personal data processing has brought about new challenges.

Technology should be used to encourage the free flow of personal data, and ensure a high standard of data protection.

Recital 7 - Why a New Framework*

The recent increase in the sharing of personal data means that a new data protection framework is required. This framework will:

- Encourage the development of the EU's digital economy;

- Give people control over their personal data;

- Enhance legal certainty.

Recital 8 - Integration into National Law*

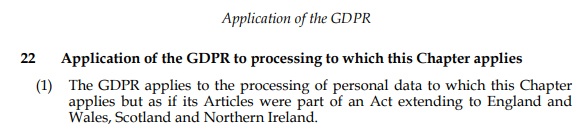

EU Member States can incorporate parts of the GDPR into their national law where necessary.

For example, the UK passed the Data Protection Act 2018, a national law which brings the GDPR on the UK's statute books.

Recital 9 - Data Protection Directive*

Under the Data Protection Directive, an older EU law which the GDPR replaces, data protection has been applied unevenly across the EU. People generally feel that their personal data is not safe online.

Data has not been flowing entirely freely across the EU. This is an obstacle to economic activity. This is because of the inconsistent application of the Data Protection Directive.

Recital 10 - Specifications in National Law*

All EU Member States should offer the same consistent level of data protection. This will enhance people's rights and allow for the free flow of data across the EU.

EU Member States can specify how the GDPR is applied via their own national law. They can make specific rules about the processing of personal data in particular circumstances, such as where:

- There is a legal obligation to process personal data;

- Personal data is processed to carry out a public task;

- Sensitive personal data is being processed.

Recital 11 - Effective Data Protection*

The only way to effectively protect personal data throughout the EU is to:

- Strengthen people's data rights;

- Increase the obligations of those who process people's personal data;

- Empower EU Member States to enforce data protection law.

Recital 12 - Powers of the European Parliament and the Council*

The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, one of the EU's founding treaties, gives the European Parliament and Council the power to make rules about the processing and protection of personal data.

Recital 13 - Necessity of the GDPR*

Some of the reasons that the GDPR is necessary are:

- To provide legal certainty and transparency for small and medium-sized businesses;

- To ensure a consistent level of legally-enforceable rights for people in all EU Member States;

- To impose the same obligations on those processing personal data across all EU Member States.

Businesses with fewer than 250 employees aren't required to follow all of the GDPR's rules regarding record-keeping. EU Member States should be conscious of how they apply the GDPR when it comes to small and medium-sized businesses.

Recital 14 - Natural and Legal Persons*

The GDPR applies to personal data of natural persons, but not legal persons.

The name of a business might contain a natural person's name and/or address, e.g. "Tom Jones 1st Avenue Web Development Services Inc." In this context, this would be personal data of a legal person, and the GDPR wouldn't apply to it.

Recital 15 - Unstructured Personal Data*

Data protection should apply no matter what technology is used. The GDPR applies wherever personal data is collected automatically or as part of a filing system. Where personal data is stored in an unstructured way, it might not be covered by the GDPR.

Recital 16 - National Security*

The GDPR doesn't apply to issues that fall outside the scope of Union law, such as the processing of personal data by Member States when carrying out issues of national security.

Recital 17 - Adaptation of Existing EU Law*

Any other EU laws which cover the processing of personal data should be adapted so that they're compatible with the GDPR.

Recital 18 - Personal or Household Activity*

The GDPR doesn't apply to purely personal or domestic activity, for example keeping an address book or using a social media account.

Recital 19 - Criminal Investigations*

The GDPR doesn't generally apply to the investigation or prosecution of crime, which is covered by the Law Enforcement Directive, another EU law. However, there are some circumstances where processing of personal data in relation to criminal investigations might be within the scope of the GDPR. In such circumstances, EU Member States can restrict individuals' data rights in the interests of public security.

Recital 20 - Judicial Activity*

Although the GDPR does apply to the activities of courts in certain contexts, supervisory authorities shouldn't interfere with courts when they're acting in a judicial capacity. The data processing activities of judges can be monitored by bodies within the judicial system itself. This is so that they remain independent.

Recital 21 - Intermediary Service Providers' Liability*

Under the Electronic Commerce Directive, another EU law, certain rules apply to Internet Service Providers (ISPs) (known as "intermediary service providers" in EU legislation). For example, they aren't legally responsible for the information that passes through their networks. The GDPR doesn't affect these rules.

Recital 22 - Establishment in the EU*

The GDPR applies to the processing of personal data by any person or organization established anywhere in the EU, regardless of whether the actual act of processing takes place within the EU.

Recital 23 - Offering Goods and Services in the EU*

The GDPR applies to you if you are processing the personal data of people in the EU with the aim of offering them goods or services (whether paid or free). This is true whether you are established in the EU or not.

The mere fact that your website is accessible in the EU doesn't, by itself, mean that you'll necessarily fall into this criteria. There should be some evidence that you intend for EU residents to use your service. This will be context-dependent, but some examples include:

- Using a language spoken in an EU Member State;

- Offering goods in an EU currency;

- Making references to EU customers.

Recital 24 - Monitoring Behavior in the EU*

The GDPR applies to you if you are monitoring the behavior of people in the EU, whether you are established in the EU or not.

In general, if you're profiling someone in order to try to predict their future behavior or preferences, this is a form of monitoring. This might include tracking internet activity through the use of targeted cookies. Targeted advertising generally requires profiling and monitoring, and thus falls within the scope of the GDPR.

Recital 25 - International Contexts*

The GDPR applies to EU diplomats working outside of the EU, or any other situation where EU law applies.

Recital 26 - Anonymous Data*

Because the GDPR only applies to personal data - that is, information that can be used to identify a person - it doesn't apply to data that has been properly anonymized.

It's important to consider whether the data could still be used to identify a person using technology, for example by de-encryption. But generally speaking, anonymous data used for research or statistical purposes doesn't fall within the scope of the GDPR.

Recital 27 - Deceased Individuals*

The GDPR doesn't apply to the personal data of deceased people.

Recital 28 - Pseudonymization*

The GDPR refers frequently to the process of pseudonymization as a good way of protecting people's personal data. It should be made clear that whilst this is a good method of data protection, it's not the only acceptable method.

Recital 29 - Pseudonymization Within One Controller*

Pseudonymization of personal data can be performed by the same data controller that's processing that personal data for other purposes, so long as appropriate safeguards are in place to ensure that unauthorized people cannot identify who the personal data refers to.

Recital 30 - Online Personal Data*

The following things can be used to identify a person, and therefore might be considered personal data:

- IP addresses;

- Cookies;

- RFID tags.

The UK's supervisory authority, the Information Commissioner's Office (ICO), also suggests:

- MAC addresses;

- Advertising IDs;

- Pixel tags;

- Account handles;

- Device fingerprints.

Anything that leaves a trace online might be used to help identify a person.

Here's how Vistage gives information about its use of pixel tags in its Privacy Policy:

![]()

Recital 31 - Public Authorities*

The GDPR doesn't apply to certain public authorities if they're processing personal data to carry out certain public tasks. Such public authorities include:

- Tax offices;

- Customs authorities;

- Financial regulators.

This isn't to say that such bodies are entirely exempt to GDPR, but that they shouldn't fall within its remit when they're carrying out tasks under a legal obligation. There will usually be separate rules around this type of data processing that they'll have to follow.

You can provide such public authorities with people's personal data if they request it in the proper way. They shouldn't normally be asking for all of the personal data you're storing.

Recital 32 - Conditions for Consent*

The GDPR sets out new conditions for consent. Consent must be:

- Freely given;

- Specific;

- Informed;

- Unambiguous.

Consent can be given in writing, orally, or via electronic means. Some examples of where consent might be properly gained include:

- Ticking a box ("I agree") on a website;

- Actively turning on particular settings within an application;

- Giving a written statement of agreement with a set of terms.

The following things do not count as consent:

- Silence;

- Failing to untick a pre-ticked box;

- Inactivity.

Consent should be 'granular,' meaning that where you are seeking to use personal data for more than one type of data processing, or more than one purpose, you must earn consent for each different use.

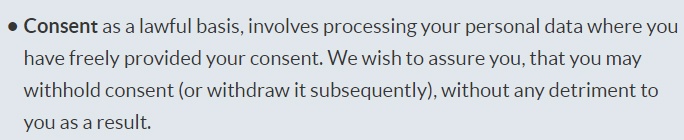

Here's how cereal company Weetabix explains its position on consent in its Privacy Policy

Recital 33 - Scientific Research*

If you're processing personal data in the context of scientific research, you might not know the exact purpose of the personal data at the time you're collecting it. Therefore, it's important that the people whose personal data you're collecting are allowed to specify which areas of scientific research it can be used in.

Recital 34 - Genetic Data*

The GDPR makes reference to genetic data. This is defined as a person's inherited or acquired characteristics, which result from certain methods of analyzing a biological sample (or an equivalent), in particular:

- Chromosomal analysis;

- DNA analysis;

- RNA analysis.

Recital 35 - Health Data*

Health data refers to any data about a person's past, present or future state of physical or mental health. Some examples given include:

- Data collected in connection with the Patients' Rights Directive, another EU law;

- An ID number used in by healthcare system;

- Information derived from genetic or other biological testing;

- Medical records or any information on medical treatment.

Recital 36 - Main Establishment*

A data controller's main establishment in the EU should be the place where it makes decisions about how and why to process personal data. This is not necessarily the same place where the data processing occurs. Rather, it's the place where the data processing activities are managed.

A data processor's main establishment in the EU should be wherever it has its central administration in the EU. If it has no central administration, then it should the main place that it does its data processing.

In a case involving both a data controller and a data processor, the lead supervisory authority should be the supervisory authority of the Member State in which the data controller has its main establishment. If the data processor has a different supervisory authority, it should cooperate with the lead supervisory authority via the cooperation mechanism.

Recital 37 - Groups of Undertakings*

A group of undertakings can consist of an undertaking, plus some other undertakings whose data processing it controls.

In EU law, the term "undertaking" refers to some enterprise, organization or business offering goods or services or engaged in economic activity (whether for profit or not).

Recital 38 - Children's Personal Data*

Children's personal data is specially protected, especially with regard to certain activities, including:

- Marketing;

- Creating online profiles;

- Services specifically aimed at children.

While parental consent is required for some activities under the GDPR, this shouldn't apply to certain counseling services offered directly to children.

Recital 39 - Data Processing Principles*

Data processing should adhere to certain principles.

Lawfulness, fairness and transparency:

- Inform people about how and why their data is being processed, at the time that their personal data is collected.

- Provide Information about data processing in plain and simple language, particularly with regard to the identity and contact details your organization.

- Make people aware of any risks involved in the processing of their personal data;

- Make people aware of their rights in relation to their personal data, and the safeguards in place to protect it.

Purpose limitation:

- Only process personal data for a specific purpose. You should collect the personal data you need to fulfill that purpose adequately.

- Only process personal data if you have no other reasonable way of fulfilling whatever purpose you have in mind.

Data minimization:

- Only process the minimum amount of personal data you need to fulfill a particular purpose;

Accuracy:

- Make sure you erase or rectify inaccurate data.

Storage limitation:

- Only store personal data for the minimum amount of time necessary. Keep this period under review.

Integrity and confidentiality:

- Keep the personal data you're processing safe and confidential.

Recital 40 - Lawful Bases*

Data processing must take place on a lawful basis, such as:

- Consent;

- Contract;

- Legal obligation;

- Vital interests;

- Public task;

- Legitimate interests.

Recital 41 - Defining "Legal"*

When the GDPR refers to a "legal basis," it doesn't necessarily mean a basis in any particular piece of legislation - although in the legal systems of certain EU Member States this might be a necessary part of the definition. In such a case, this legislation should be easily understood by the people who are subject to it.

Recital 42 - Consent*

If you're relying on a person's consent as your lawful basis for processing their personal data, you need to be able to demonstrate that you've gained it.

People need to be aware of what they've consented to. If you're asking someone to consent to a pre-written statement, this statement must be:

- Easily accessible;

- Written in clear and plain language;

- Free of any unfair terms.

Consent must be informed. This means that people need to at least know who is processing their data and why.

Consent must be freely given. This means people must have a genuine choice to consent. They should be able to easily withdraw their consent, without suffering any negative consequences.

Recital 43 - Freely Given Consent*

Consent should be freely given, and must not be coercive. It might not be considered freely given if:

- There is a clear imbalance of power between the data controller and the individual, for example where the controller is a public authority;

- The fulfillment of a contract depends on consent to process personal data for a particular service. If providing the service that requires consent isn't necessary for the sake of fulfilling the contract, a separate option should be given for consenting to this.

Recital 44 - Contract*

If you need to process someone's personal data to fulfill or enter into a contract with them, it's legal to do so. This is a separate lawful basis from consent.

Recital 45 - Legal Obligation and Public Task*

If you're relying on a legal obligation or public task as your basis for processing personal data, the obligation or task should have some basis in the law of the EU or an EU Member State.

To satisfy this requirement, the GDPR doesn't require an individual law for each act or type of processing. A law that covers various types of processing in the context of the GDPR should suffice if it complies with the GDPR's principles of data processing.

EU Member States can decide whether a "public task" has to be carried out by an actual state authority or some other organization or person that has legal powers.

Recital 46 - Vital Interests*

If you need to process someone's personal data to save a life (theirs or another person's), it's legal to do so. Processing personal data on this lawful basis should be a last resort, only to be used if they are unable to consent.

Some examples of situations where this might be necessary include:

- Monitoring epidemics;

- Natural disasters;

- Man-made disasters.

Recital 47 - Legitimate Interests*

A data controller may have a legitimate interest in processing personal data, but only where its interests are not overridden by the rights of the person whose personal data it wants to process.

For example, a data controller might have a legitimate interest in processing the personal data of a client or regular customer. In this case, the controller might not have to rely on consent or another legal basis to carry out the processing. The context of the relationship is important.

When seeking to rely on its legitimate interests as a lawful basis for processing personal data, the data controller will always need to consider what the person would reasonably expect. If the person wouldn't reasonably expect their personal data to be processed in a particular context, this expectation will override the contoller's legitimate interest. The applies even where the person is a client or regular customer of the controller.

Legitimate interests is a very broad basis for processing personal data. It might be a lawful basis for fraud prevention or even direct marketing. It all depends on a person's rights in a particular context.

Recital 48 - Sharing Personal Data as a Legitimate Interest*

A data controller might have a legitimate interest to share personal data within a group of other controllers. This group of controllers would have to fit the definition of a "group of undertakings" as defined at Recital 37.

Any such data-sharing arrangement would still have to comply with the rules around transferring personal data to non-EU countries, if relevant.

Recital 49 - Ensuring Network Security as a Legitimate Interest*

Ensuring data protection or the security of a network might represent a legitimate interest in processing personal data.

A data controller needs to be confident that their networks are secure and should be testing them regularly. Where this requires them to process personal data, they have a legitimate interest to do so.

Recital 50 - Further Processing*

You should only process personal data for the same reason and on the same lawful basis for which you collected it.

There may be exceptions to this if national law permits it. Some types of processing are considered compatible with one another. This means that further processing of personal data on a particular basis might be lawful, depending on the original reason it was collected.

For example, the following purposes for processing personal data are considered compatible:

- Archiving in the public interest;

- Scientific or historical research;

- Producing statistics.

An assessment of whether purposes are compatible must always take certain things into account, for example:

- The nature of a person's personal data;

- What the person would reasonably expect;

- Appropriate safeguards.

Sometimes a controller can engage in further processing even if the new purpose is not compatible with the old one. For example, where the person has consented to further processing, or where it's being carried out in the public interest. Further processing of criminal conviction data might be in the legitimate interests of a public authority.

When considering the lawfulness of further processing, always keep the GDPR's data processing principles in mind.

Recital 51 - Special Category Data*

The high degree of risk involved in processing special category (sensitive) personal data means that special safeguards are required.

The rule is that by default, special category data should not be processed. There are specific exceptions to this rule, such as where:

- It is done in pursuit of a public task authorized by national law;

- A person has explicitly consented to it in relation to a specific purpose;

- It is in the legitimate interests of an organization that serves to protect people's rights.

The use of the term "racial origin" in the GDPR doesn't mean that the EU necessarily accepts that there are distinct races of humans.

Photographs are only special category data if they are biometric data, i.e. they have been processed via special technology.

Recital 52 - Valid Reasons to Process Special Category Data*

Processing special category data is, by default, not allowed. There are some exceptions to this, where it is legal and performed under special safeguards, for example:

- In the fields of employment law or social protection law;

- In relation to monitoring health or preventing contagious diseases;

- In the context of a legal claim.

Recital 53 - Special Category Health Data*

Special category data might be processed in the field of health, but only where it benefits wider society. For example:

- In the management of a health or social care system, or allowing health systems to operate across borders.

- For monitoring health or providing alerts;

- For archiving or scientific research purposes.

The GDPR aims to harmonize the conditions under which special category data can be processed for health purposes - particularly where it's subject to professional confidentiality. EU Member States can introduce additional laws around protection people's rights in relation to their health data - so long as these laws don't stop data from flowing freely around the EU.

Recital 54 - Public Health*

It may be necessary to process special category data without consent in the context of public health. The definition of public health includes data relating to:

- Health status;

- Morbidity and disability;

- Healthcare needs;

- Healthcare funding;

- Access to healthcare.

Third party processing for purposes such as employment, insurance or banking doesn't fall into this category of "public health."

Recital 55 - Religious Communities*

Where public authorities process personal data in order to achieve the aims of religious associations, this is in the public interest.

Recital 56 - Electoral Data*

Processing personal data for producing opinion polls during elections can be justified in the public interest - if there are appropriate safeguards in place.

Recital 57 - Identification*

If the reasons you're processing personal data don't require you to know who the data you're processing actually belongs to, you aren't required to find out.

However, if you have the personal data of an unknown person, that person should still be allowed to exercise their data rights. If they provide you with more information in order to identify themselves, for example, their login credentials, you should use this to identify them and help facilitate their data rights.

Recital 58 - Transparency and Your Privacy Policy*

All the information you provide about your data processing needs to be easy to access and easy to understand. You must use plain and simple language. You should provide this information on your website. This can be done in a Privacy Policy.

Here's an example of a short and simple summary of a Privacy Policy provided before the full version by Blackbaud:

Sometimes it can be difficult for people to understand who is collecting their personal data, and why they're collecting it. So, it's particularly important to be transparent if you're engaged in online advertising.

If your services are aimed at children, your Privacy Policy should be comprehensible to children.

Recital 59 - Facilitating Data Rights*

You should have systems in place to help people exercise their data rights. This includes a way to allow people to get access to their data, and also request that you rectify or erase it.

If you're processing personal data electronically, your users should be able to make such requests electronically.

You must respond to such requests as soon as reasonably possible, and within one month at most. If you're refusing a request, you need to explain why.

Recital 60 - Providing Information*

You should tell people:

- The ways you're processing personal data and the reasons you're processing it;

- Whether you're engaged in profiling, and what this means for them;

- The reasons you're asking them to provide their personal data, and what might happen if they don't.

Here's how Nestle explains these points to its users in its Privacy Policy:

You can make use of standardized icons in your Privacy Policy. They should be "readable" by devices. Here's an example of how to use icons from the UK's supervisory authority, the Information Commissioner's Office (ICO):

![]()

Recital 61 - When to Provide Information*

The rules on when you need to provide information about your processing activities vary depending on context. For example:

- If you're collecting someone's personal data directly from them, you need to present your Privacy Policy at the time of collection.

- If you've obtained someone's personal data from a third party, you need to send them your Privacy Policy within a reasonable period.

- If you need to share someone's personal data, you should tell them any relevant information at the point at which you share it.

- If you need to process someone's personal data in a way other than the one for which you collected it, you should give them all the relevant information about the new processing before you start.

- If you can't determine where you obtained someone's personal data because it comes from various different sources, you should provide general information.

Recital 62 - No Requirement to Provide Information*

You might not need to provide information about your processing where:

- The person already has this information;

- The processing is expressly laid down by law;

- Providing the information would involve an unreasonable effort, for example, if the processing is related to archiving or statistical purposes.

The above might not apply if you're processing children's personal data.

Recital 63 - Access Requests*

Anyone whose personal data you're processing has a right to access that data. They should be able to access it easily and as often as they desire. This allows them to check that you're processing their personal data lawfully.

Here's how legal firm PwC informs its users about this right in its Privacy Statement:

You should be able to give your users information about your processing on request, including:

- Why you're processing their personal data;

- How long you'll be processing it for (if known);

- Who you'll be sharing it with;

- Information about any automated decision-making you engage in.

You should try to provide some remote system by which your users can access their personal data - but ensure that your other users' personal data remains secure.

If you're processing a lot of someone's personal data, you can ask them to be specific about the data that they want you to reveal to them.

Recital 64 - ID Requirements*

You should take steps to verify anyone who has made a request to access their personal data. This may include asking them for ID. You can't store people's ID for this purpose.

Recital 65 - Rectification and Erasure Requests*

Anyone whose personal data you're processing has a right to request that it's rectified or erased. This right to erasure is known as "the right to be forgotten."

You must erase your users' personal data on request if:

- You no longer need it for the reason you obtained it;

- They've withdrawn consent;

- You're processing it unlawfully;

An example of a specific situation is where a person made comments on a social media account and now wants them removed.

There are certain reasons you might refuse to erase someone's personal data, for example:

- You are exercising your freedom of expression;

- You need to comply with the law;

- You're a public authority carrying out a task in the public interest;

- You need it for a legal claim.

Recital 66 - Erasing a Person's Online Presence*

If you have made someone's personal data public online, and they wish to exercise their right to be forgotten, you're responsible for informing any third parties who might have links to or copies of that personal data.

Recital 67 - Restriction Requests*

Anyone whose personal data you're processing has the right to request a restriction of the ways you're processing their personal data.

Some examples of ways that you might comply with this request include:

- Moving the data to another system;

- Making the data temporarily inaccessible;

- Temporarily removing the data from your website.

This function should be built into databases that are used for processing personal data.

Recital 68 - Portability Requests*

Anyone whose personal data you're processing has the right to request a copy of their personal data in a portable, commonly used electronic format so that they can give it to another data controller if they wish to.

This applies either where the person has consented to your processing their personal data, or you're doing so under contract. It doesn't apply under any other lawful basis.

You must be careful not to include anyone else's personal data in this file.

By making a request for data portability, a person doesn't forgo their right to erasure.

Where possible, you should carry out a requested transfer to another data controller yourself.

Recital 69 - Objection to Processing*

If you're processing someone's personal data on the lawful basis of a public task, official authority or legitimate interests, they have the right to object to your processing. If you can demonstrate an overriding legitimate interest in continuing to process their personal data, you may able to refuse to stop.

Farewill makes this clear in its Privacy Policy:

Recital 70 - Objection to Direct Marketing*

People have an absolute right to object to direct marketing, and you must stop if they do object.

You must make people aware of this right. You must present this information separately from other information.

Recital 71 - Automated Decision-Making*

People have the right not to have certain types of decisions made about them by automated means. These types of decisions might involve "profiling." In the GDPR, profiling refers to the act of analyzing someone's past behavior or characteristics in order to predict their future behavior.

The right to object to automated decision-making exists where very serious decisions are made, such as the denial of credit or the denial of a job interview. Such processing is generally not allowed except under very specific conditions, and is never allowed in the case of children.

If you are carrying out this type of data processing, there is potential for it to go wrong. Because of this, you'll need safeguards in place. These safeguards should include the option of having a human review the decisions and give explanations for them.

Recital 72 - Guidance for Profiling*

The GDPR applies to profiling. The European Data Protection Board, referred to throughout the GDPR as "the Board," can issue guidelines on profiling.

Recital 73 - Suspension of Data Rights*

Under certain circumstances, EU Member States can suspend or restrict people's ability to exercise the GDPR's eight data rights. This is only when it's necessary in certain extreme situations, such as:

- Protecting public security;

- Following a natural or manmade disaster;

- In the context of crime and punishment;

Such restrictions on these rights should only occur where sanctioned by EU-recognized human rights law.

Recital 74 - Controllers' Liability*

Data controllers are legally liable for their acts of data processing. They must comply with the GDPR and be able to demonstrate that they're doing so.

Recital 75 - Risks*

The GDPR refers to data processing that might cause risks to people's rights and freedoms. Some examples of particular risks that might arise from processing include:

- Discrimination;

- Identity theft or fraud;

- Financial loss;

- Reputational damage;

- Confidentiality breaches;

- Revealing of sensitive information.

Recital 76 - Assessment of Risk*

Risk should be assessed objectively. Factors such as the scope and context of the processing should be considered. You should establish whether your data processing involves risk, or if it is high risk.

Recital 77 - Guidance on Assessing Risk*

The GDPR suggests some mechanisms that can be used to advise data controllers and processors about the risks involved in processing personal data, and how to safeguard against them. These include:

- Codes of conduct;

- Certification;

- Specific guidance from a company's Data Protection Officer;

- General guidance issued by the European Data Protection Board.

Recital 78 - Technical Measures*

If you're processing personal data, the GDPR requires that you take particular technical and organizational measures to protect your users. One of the key concepts in the GDPR is "data protection by design and by default."

Data protection measures should be built into your data processing methods and systems. Such measures might include:

- Pseudonymization;

- Data minimization;

- Allowing your users to monitor how you process their data.

Anyone designing products or services that enable the processing of personal data is expected to design them in such a way that respects the principles of data protection.

Recital 79 - Allocating Responsibilities*

Where a data processing operation is shared between a group of data controllers, or where a data controller hires a data processor, it should be clear who is responsible for fulfilling which obligations under the GDPR.

Recital 80 - Nominating a Representative*

If your organization is based outside of the EU and is offering goods or services to people in the EU or monitoring their behavior, you are accountable under the GDPR. You should designate a person to represent you in the EU. You don't need to do this if:

- You're only processing personal data occasionally;

- You're not processing special category data, criminal conviction data, or doing other high-risk data processing on a large scale.

This representative will act on your organization's behalf and liaise with supervisory authorities, and will not be held legally liable for any compliance issues.

Here's how Merriam-Webster gives the details of the EU representative in its Privacy Policy:

Recital 81 - Data Processors*

Data controllers should only hire data processors that can demonstrate their GDPR compliance. One way they might partly demonstrate this is by showing that they adhere to an approved code of conduct or hold certifications.

Data controllers must have a contract with their processors that gives information about the nature of the job, including:

- The reason for the processing;

- The type of personal data involved;

- Whose data is being processed (broadly speaking);

- The risks involved.

Supervisory bodies and the European Commission should offer standard contractual clauses that data controllers and processors can use in such a contract.

When the data processor has finished their job, they should usually return the personal data to their controller or erase it at the choice and direction of the controller.

Recital 82 - Keeping Records*

You should keep records of your data processing activities. Supervisory authorities may need to see these records, and they must be made available if so.

Recital 83 - Ensuring Security*

You should evaluate the risks involved in your data processing activities and take measures to guard against them. Consider the risks associated with your data processing. These might include:

- Accidentally destroying personal data;

- Losing it;

- Allowing unauthorized access to it.

Recital 84 - Data Protection Impact Assessment*

If you're engaged in risky data processing activities, you may need to carry out a data protection impact assessment. Consider:

- Where and when the risk arises;

- The nature of the risk:

- How severe it is.

As a result of this impact assessment, you should understand what measures you need to put in place to ensure your processing is secure.

If you're in any doubt about your ability to appropriately mitigate against the risks associated with your data processing activities, you need to consult with your supervisory authority before processing.

Recital 85 - Data Breach Notification*

If you become aware that there has been a security breach and that some of your users' personal data has potentially been compromised, you need to inform your supervisory authority right away. This should be done within 72 hours at the latest. If for some reason it will take longer, you need to explain the reason for the delay.

You might not need to report a breach if it's unlikely to represent a serious risk to your users. Bear in mind that you are accountable under the GDPR.

Recital 86 - Direct Notification to Users*

If you become aware that there has been a high-risk security breach and that some of your users' personal data has potentially been compromised, you need to inform your users right away. You should do this in cooperation with your supervisory authority.

You need to let people know the nature of the breach and what they might do to mitigate against the risks.

Recital 87 - Prompt Notification of Data Breaches*

Data protection and security of data processing are very important, and there are penalties for failing to protect people's personal data under the GDPR. If you have suffered a data breach, it is crucial that you know about it as early as possible. This means taking the appropriate organizational and technical measures to ensure this.

Reporting promptly is important because the supervisory authority might be able to act in such a way as to limit the damage caused by a breach. Whether you reported the incident promptly will be investigated and noted.

Recital 88 - Rules About Data Breach Notification*

Certain bodies may be tasked with producing rules about the way that data breaches are reported. These rules need to take into account the context in which a data breach has occurred.

It may be, for example, that the compromised personal data had been pseudonymized. This means that it is unlikely to be used for fraud.

It may also be in the legitimate interests of law enforcement authorities not to disclose a breach immediately if doing so might prevent them from bringing the culprit to justice.

Recital 89 - Changes to Reporting Requirements*

The old Data Protection Directive, which the GDPR replaces, required all personal data processing activities to be reported to a supervisory authority. This was an unnecessarily burdensome requirement that didn't necessarily improve the protection of personal data. Therefore, this is no longer a requirement under the GDPR.

The requirement has been replaced with a focus on having effective procedures and mechanisms in place to protect data processing operations that come with high risks to rights and freedoms of individuals.

Recital 90 - Mandatory Data Protection Impact Assessments*

If you're a controller and engaged in particularly high-risk data processing operations, you should carry out a data protection impact assessment.

Consider:

- When and where the risk arises;

- The nature of the risk;

- How severe it is.

Consider what technical and organizational measures you can implement to safeguard and mitigate against risk, and how you will comply with the GDPR.

Recital 91 - Circumstances Requiring an Impact Assessment*

It is particularly important that you carry out a data protection impact assessment if you're processing personal data in particular contexts, including if you're:

- Processing a particularly large volume of personal data;

- Using new technology;

- Processing in such a way that it will be difficult to let your users know about their data rights;

- Making highly important automated decisions involving profiling;

- Processing large quantities of special category data;

- Monitoring a public area on a large scale.

A data protection impact assessment isn't mandatory if the data processing is small-scale, for example, performed by an individual doctor or lawyer.

Recital 92 - Large-Scale Data Protection Impact Assessment*

Under certain circumstances, it's possible for a data protection impact assessment to be broad enough to cover the activities of several data controllers, or even a whole industry.

Recital 93 - State-Regulated Data Protection Impact Assessments*

Where an EU Member State regulates a particular type of data processing, it may wish to carry out a large-scale data protection impact assessment before the processing is allowed to take place.

Recital 94 - Consulting a Supervisory Authority*

Where your data protection impact assessment reveals that the data processing you're planning is particularly risky, and you can't work out a way to guard against that risk effectively, you'll need to consult with your supervisory authority before processing.

The supervisory authority should respond to you within a specified time. If it doesn't respond to you within this time-frame, this doesn't mean that you can just proceed with your planned processing.

After the consultation with the supervisory authority has taken place, you can submit a new data protection impact assessment to it for approval.

Recital 95 - Assistance From Your Data Processor*

Where a data controller is conducting a data protection impact assessment, their data processor is expected to help them with this if necessary or requested by the data controller.

Recital 96 - Lawmaking and the Supervisory Authority*

The supervisory authority should be involved when any laws and regulations about processing personal data are being drawn up.

Recital 97 - Data Protection Officer*

If you're a data controller, you might need to designate a data protection officer, including if you're:

- A public authority (except courts when acting in a judicial capacity);

- Monitoring people on a large scale as your core activity;

- Processing a large volume of special category or criminal record data as a core activity.

You don't need a data protection officer if you're only processing personal data to support your main activities.

Your data protection officer can be someone already employed within your company, but they must have an expert-level knowledge of data protection and the GDPR and they need to be able to act with complete independence.

Recital 98 - Codes of Conduct*

EU Member States should encourage certain bodies, such as associations of small or medium-sized enterprises, to draw up codes of conduct which instruct their members on how to comply with the GDPR.

These codes of conduct will serve to set out the specific obligations of particular types of data controllers and processors, in the context of the particular risks involved in their data processing activities.

Recital 99 - Consultation for Codes of Conduct*

When drawing up a code of conduct, you should try to consult with those groups and individuals who have some stake in it. Listen carefully to their opinions.

Recital 100 - Certification Schemes*

There should be certificates available for those organizations and individuals who can demonstrate their compliance with the GDPR.

Recital 101 - International Data Transfers*

New challenges have emerged due to the general increase in personal data traffic. These challenges are particularly apparent when trying to safely transfer personal data from the EU to third (non-EU) countries.

Nonetheless, data transfers to third countries must be GDPR-compliant. They cannot take place if they are not.

Recital 102 - International Data Transfer Agreements*

The EU has some international agreements in place with third (non-EU) countries regarding data transfer arrangements. These aren't overridden by the GDPR.

EU Member States can also enter into such agreements so long as they are compatible with the GDPR and include appropriate levels of protection of the fundamental rights of data subjects.

Recital 103 - Third Country Adequacy Decisions*

If the European Commission has given approval to a third country's data processing practices, affirming that they are adequate, you can transfer personal data from the EU to this country without any additional permissions being required.

Here's the Commission's list as of 30 September 2018:

The Commission can decide that a third country's data processing practices are no longer adequate and revoke its decision after it has explained their reasoning to the country concerned.

Recital 104 - Adequacy Decision Conditions*

The European Commission will take certain factors into account when deciding whether a third country's data protection practices are good enough to allow data transfers from the EU.

The basic requirements are that the third country's data protection practices are:

- At least as strong as the EU's;

- Backed up by appropriate laws and regulations and enforced by a cooperative supervisory authority;

- Operating within a democratic legal framework that allows individuals to exercise their data rights.

Recital 105 - Third Countries and International Agreements*

Whether a third country is signed up to any international data protection agreements would be a relevant factor for the European Commission in deciding whether data transfers should be automatically allowed to that country.

Of particular relevance is the Council of Europe's Convention for the Protection of Individuals with regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data (Convention 108).

Recital 106 - Reviews of Third Countries' Data Protection*

The European Commission should carry out regular reviews of the data protection practices of third countries that it has deemed adequate for data transfers. These reviews should take the opinions of the European Parliament and Council into account.

Recital 107 - Amendment of Adequacy Decisions*

The European Commission has the power to decide that a third country has adequate data processing practices. This means that personal data to be transfers out of the EU into that country are permitted by default. None of the GDPR's additional safeguarding requirements apply.

The Commission also has the power to reverse or amend this decision if it deems that the situation has changed. At this point, personal data transfers to this country will require appropriate safeguards again.

Recital 108 - Data Transfer Safeguards*

You may wish to transfer personal data from the EU to a country that has not been deemed "adequate" for transfers by the European Commission. If so, you'll need to put particular safeguards in place before you can do this.

Such safeguards fall into the following categories:

- Binding corporate rules;

- Standard data protection clauses (issued by a supervisory authority or by the European Commission);

- Standard contractual clauses (issued by a supervisory authority);

- Administrative agreements (such as a memorandum of understanding) between public bodies. The supervisory authority needs to give authorization for data transfers for any administrative agreements that aren't legally binding.

The safeguards should ensure that the rights of the people whose personal data is being transferred are protected. In particular, they should be able to take their case to court if their rights are infringed regardless of whether the court is in the EU or the third country.

Recital 109 - Standard Data Protection Clauses*

The European Commission and supervisory authorities can produce standard data protection clauses that can be inserted into a contract.

Using these clauses doesn't mean that you can't also place other data protection clauses in your contract, or in a wider contract - so long as they don't contradict the standard data protection clauses you require.

Recital 110 - Binding Corporate Rules*

A group of organizations or individuals might work together in pursuit of economic activity, with one member of this group having some power over another. This is known in the GDPR as a "group of undertakings."

Sometimes a group of undertakings can transfer personal data amongst its members, even if one member is based in the EU and another is based in third country that has not been approved by the European Commission.

To do this, it must have binding corporate rules in place. These binding corporate rules should follow the principles of the GDPR, and allow the people whose personal data is being transferred to enforce their rights.

Recital 111 - Third-Country Transfer Exceptions*

The rules around international transfers should be waived in certain situations, such as where:

- A person has explicitly consented to this;

- The transfer is required for the fulfillment of a contract;

- The transfer is required in relation to a legal or regulatory claim.

Certain public interest situations might also require third-country transfers. For example, where people's personal data is compiled in a legal register that can be consulted by the public or people with legitimate interests.

In such cases, only people who have a legitimate interest must be granted access to the register. The access should only extend to the relevant parts of the register to avoid exposing the personal data of too many people.

Recital 112 - Third-Country Transfers and the Public Interest*

The rules around international transfers should be waived in certain public interest situations, for example between:

- Competition authorities;

- Customs offices;

- Financial regulators;

- Social security agencies;

- Public health agencies.

Third country data transfers are always legal where:

- They are necessary to save someone's life and gaining consent is impossible;

- Where a humanitarian organization needs to carry out tasks under international humanitarian law.

For reasons of public interest, EU Member States and the EU itself can prohibit certain types of personal data from being transferred to certain countries.

Recital 113 - Occasional and Small-Scale Data Transfers*

If you're a data controller, you may have a legitimate interest in making a certain third-country data transfer, so long as the transfer is non-repetitive and only affects a small number of people. However, you need to take certain things into account, for example:

- The types of personal data involved;

- Why you need to carry out the transfer;

- How long it will take;

- The data protection practices of the third country you're transferring to.

Always consider whether you have some other option - such a transfer really should only occur in exceptional situations.

You should let the person whose data you're transferring know about the transfer as well as the relevant supervisory authority.

Recital 114 - Data Rights and Third-Country Transfers*

Whenever you're transferring someone's personal data to a third country whose data protection practices haven't been approved by the European Commission, you must find a way of ensuring that they can exercise their data rights once the transfer is complete.

Recital 115 - Laws of Third Countries that Contradict the GDPR*

In certain countries, there are data processing laws that supposedly apply to non-nationals. A situation might arise where an EU citizen is told to transfer personal data by a third country's court.

Where such a demand is made and the transfer would be illegal under the GDPR, it should not be considered lawful. It might even contradict international law. Therefore, the person should only comply where the rules around third-country data transfers are met.

Recital 116 - Cooperation Between Supervisory Authorities*

It's particularly difficult for people to exercise their data rights in the case of cross-border data transfers. Supervisory authorities might find it difficult to investigate complaints and exercise their powers outside of their own EU Member State.

In light of this, supervisory authorities need to work together. There should be a spirit of cooperation between them, and legal and administrative mechanisms should be put in place to facilitate this cooperation.

Recital 117 - Establishing Supervisory Authorities*

Each EU Member State must establish and empower at least one supervisory authority that will exercise powers with complete independence.

Recital 118 - Monitoring Supervisory Authorities*

While they should be able to act independently, supervisory authorities can have their budgets monitored and have legal claims brought against them.

Recital 119 - Multiple Supervisory Authorities*

If an EU Member State has established more than one supervisory authority, it must pass laws to ensure that they all comply with the GDPR's consistency mechanism. One of the supervisory authorities should be designated to take the lead on this.

Recital 120 - Providing Resources for Supervisory Authorities*

A supervisory authority must have all the resources it needs to carry out its tasks. This includes money, people and premises. It should have its own annual and public budget which can be part of the overall national or state budget.

Recital 121 - Membership of Supervisory Authorities*

The process of appointing members of supervisory authorities should be set out in national law. It should be a transparent process that's carried out by a state institution such as a country's parliament or government.

Members of supervisory authorities must:

- Act with integrity;

- Not do anything that isn't in keeping with their duties;

- Not take on any outside jobs or voluntary roles that are incompatible with their membership.

The supervisory authority should have its own staff team who are only to be instructed by the supervisory authority.

Recital 122 - Responsibilities of Supervisory Authorities*

A supervisory authority must have the power and ability to carry out its duties under the GDPR. It needs to have the power and abilities to take effective action over:

- The activities of data controllers and processors established within its EU Member State;

- The processing of personal data by public bodies acting in the public interest;

- Any processing of the personal data belonging to people in its EU Member State, even when performed from third countries.

A supervisory authority's duties include:

- Handling complaints about data protection issues;

- Investigating and reporting on GDPR-compliance;

- Promoting data protection awareness.

Recital 123 - Freedom of Cooperation for Supervisory Authorities*

Supervisory authorities should be free to cooperate with each other and with the European Commission without any specific agreements on this made between Member States.

Recital 124 - Lead Supervisory Authority*

Certain personal data processing operations will take place, or affect people, across multiple EU Member States. For such operations, a lead supervisory authority is required.

The lead supervisory authority should cooperate with the other supervisory authorities involved in the operation, particularly where a complaint is lodged in an EU Member State of one of the other supervisory authorities.

The European Data Protection Board can issue guidance around how supervisory authorities should cooperate during such operations.

Recital 125 - Powers of the Lead Supervisory Authority*

The GDPR grants the lead supervisory authority certain powers. It should be able to make binding decisions within the scope of these powers.

The lead supervisory authority should coordinate the other supervisory authorities involved in a data processing operation and make sure that they are all suitably involved.

Any decision to reject or partially reject a complaint ultimately falls to the supervisory authority with whom the complaint was lodged to carry out.

Recital 126 - Joint Decisions About Complaints*

A group of supervisory authorities might have to deal with a complaint about a cross-border data processing operation. In such a situation, they should work together with their lead supervisory authority to come to a joint decision.

The data controller or processor who is the subject of the complaint will have their main establishment in a particular EU Member State. The joint decision will be directed there and will be binding on the data controller or processor concerned.

Recital 127 - The "One-Stop-Shop" Mechanism*

Non-lead supervisory authorities should be able to handle local matters, even if a data controller or processor is established across multiple EU Member States, so long as the issue only affects people in the supervisory authority's own EU Member State.

The lead supervisory authority must be informed about such cases immediately. It can then decide whether to handle the case itself. It should consider whether the data controller or processor has an establishment in the supervisory authority's EU Member State.

If the lead supervisory authority does decide to handle the case, the supervisory authority that received the complaint should submit a draft decision, which the lead supervisory authority should take into account.

This is known as the "one-stop-shop" mechanism.

Recital 128 - The "One-Stop-Shop" Mechanism and Public Bodies*

The "one-stop-shop" mechanism, where a lead supervisory authority handles a complaint in another supervisory authority's Member State, should not be used when the complaint has been made against a public body acting in the public interest. Only the supervisory authority of the relevant EU Member State can handle such a complaint.

Recital 129 - Tasks of Supervisory Authorities*

All supervisory authorities should have the same tasks and powers regarding data protection. These include powers to:

- Investigate complaints and non-compliance;

- Correct and sanction in the event of non-compliance;

- Authorize and advise on data protection;

- Ban or limit data processing.

EU Member States should be able to specify other tasks for supervisory authorities, within the scope of the GDPR.

Supervisory authorities should be diligent in their investigations and consider the unique context of every complaint. Access to personal data or a company's premises may be necessary in the course of an investigation. This power of access is still subject to national law and may need to be authorized by a court.

A supervisory authority's powers should be clearly set out and justified. A supervisory authority should still be subject to legal claims like any other public body.

Other public authorities still have the right to prosecute data protection crimes.

Recital 130 - Complaints Lodged with Non-Lead Supervisory Authorities*

Where a complaint has been lodged with a supervisory authority other than the lead supervisory authority, the lead supervisory authority should operate in-line with the GDPR's cooperation and consistency mechanisms.

The opinion of the other supervisory authority with whom the complaint has been lodged is extremely important, particularly when it comes to issuing sanctions and fines.

Recital 131 - Resolution Through Settlement*

Some issues concerning cross-border data processing operations are entirely, or almost entirely, regarding matters that are contained within one EU Member State. A supervisory authority other than the lead supervisory authority might become aware of an issue of this sort within its own territory.

In such a situation, the supervisory authority should try to resolve the issue through good-natured dialogue with the data controller or processor concerned. If coming to a settlement in this way doesn't work, the supervisory authority can exercise its full range of powers.

Recital 132 - Raising Awareness*

Supervisory authorities should raise awareness about good data protection practices. Campaigns to raise awareness can be used to promote sector-specific practices among small and medium-sized organizations and to promote general education among the public.

Recital 133 - Mutual Assistance*

Supervisory authorities should help each other wherever possible. If one supervisory authority has asked another for help and has not received it within a month, it can pass a provisional measure - a temporary order with legal effect.

Recital 134 - Supervisory Authority Joint Operations*

Supervisory authorities should work together in joint operations where appropriate. If one supervisory authority requests this of another, the supervisory authority receiving the request must respond within a specified time period.

Recital 135 - Consistency Mechanism*

The GDPR calls for the establishment of a consistency mechanism to help supervisory authorities cooperate. It's particularly important to apply this mechanism where a supervisory authority intends to take action that will have legal effects on people across more than one Member State.

The European Commission can require that a matter is dealt with via the consistency mechanism. This doesn't prevent the Commission from exercising any of its other powers.

Recital 136 - European Data Protection Board Decisions*

If there is some dispute during the application of the consistency mechanism, supervisory authorities and the European Commission can ask the European Data Protection Board for an opinion. It can also give such an opinion following a majority vote of its members.

The Board can also make legally binding decisions about such disputes. These must be passed by a two-thirds majority vote among its members.

Recital 137 - Provisional Measures*

In an urgent situation where the rights and freedoms of data subjects may be impeded, a supervisory authority can pass provisional measures. These are temporary orders with legal effect and specified timeframes that should not exceed three months.

Recital 138 - Urgent Situations Across Borders*

In an emergency that is relevant across more than one Member State, joint operations can take place between supervisory authorities without the need to trigger the GDPR's consistency mechanism.

Recital 139 - European Data Protection Board*

The GDPR establishes the European Data Protection Board - an EU body with legal rights and obligations. It replaces the Article 29 Working Party. Its jobs are to:

- Help ensure that the GDPR is applied consistently;

- Advise the European Commission on data protection issues;

- Promote cooperation among supervisory authorities.

The Board consists of the head of one supervisory authority from each EU Member State, plus the European Data Protection Supervisor.

The Board should act independently. The Commission can attend its meetings but cannot vote.

Recital 140 - Secretariat of the European Data Protection Board*

The European Data Protection Supervisor provides the European Data Protection Board with a secretariat. The Secretariat works exclusively under the instruction of the Chair of the European Data Protection Board.

Recital 141 - Lodging a Complaint*

Everyone in the EU has the right to lodge a complaint with their supervisory authority if they feel that their data rights have been infringed. They also have a right to take their case to court - including if the supervisory authority rejects their complaint or fails to properly deal with it.

Investigations about the way a supervisory authority has handled a complaint are conducted by judicial review. The supervisory authority should keep the person who has made the complaint informed about:

- The progress of the investigation;

- Whether any further information is required;

- Whether any other supervisory authorities need to be involved.

Each supervisory authority should take measures such as providing complaint submission forms that can be completed electronically.

Recital 142 - Support by a Not-for-Profit*