The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is comprised of 99 Articles and 173 Recitals.

Below you'll find a summary and brief explanation of each Article of the GDPR, organized by Chapter.

We've strived to explain each Article in the most clear and simple way so you can get a basic understanding of what the Article dictates or demands.

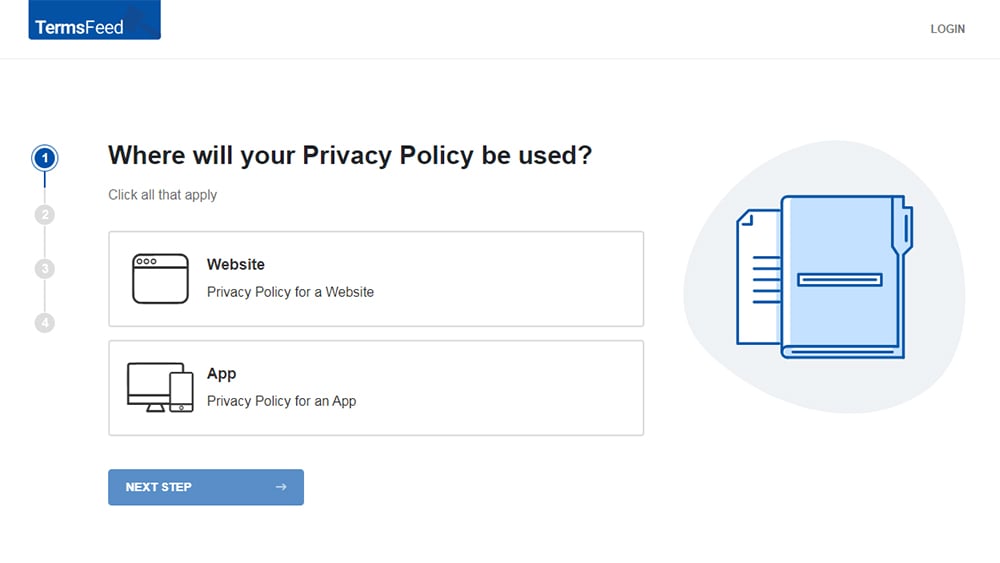

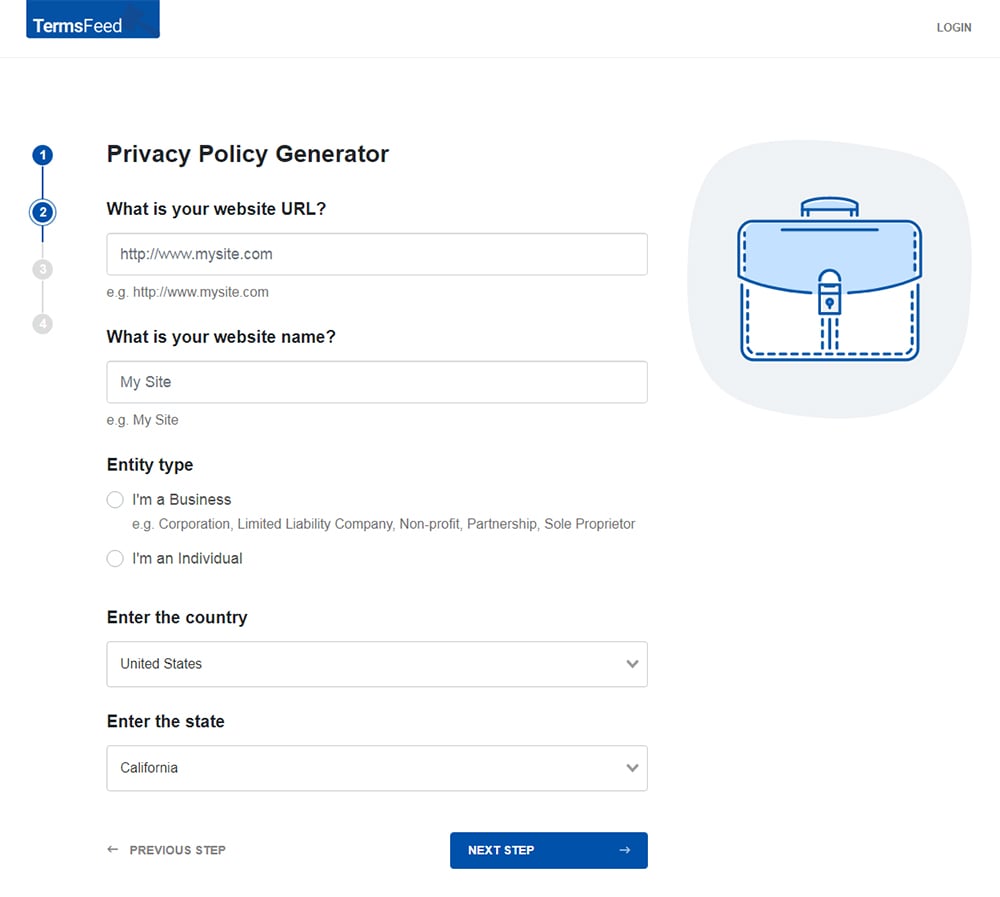

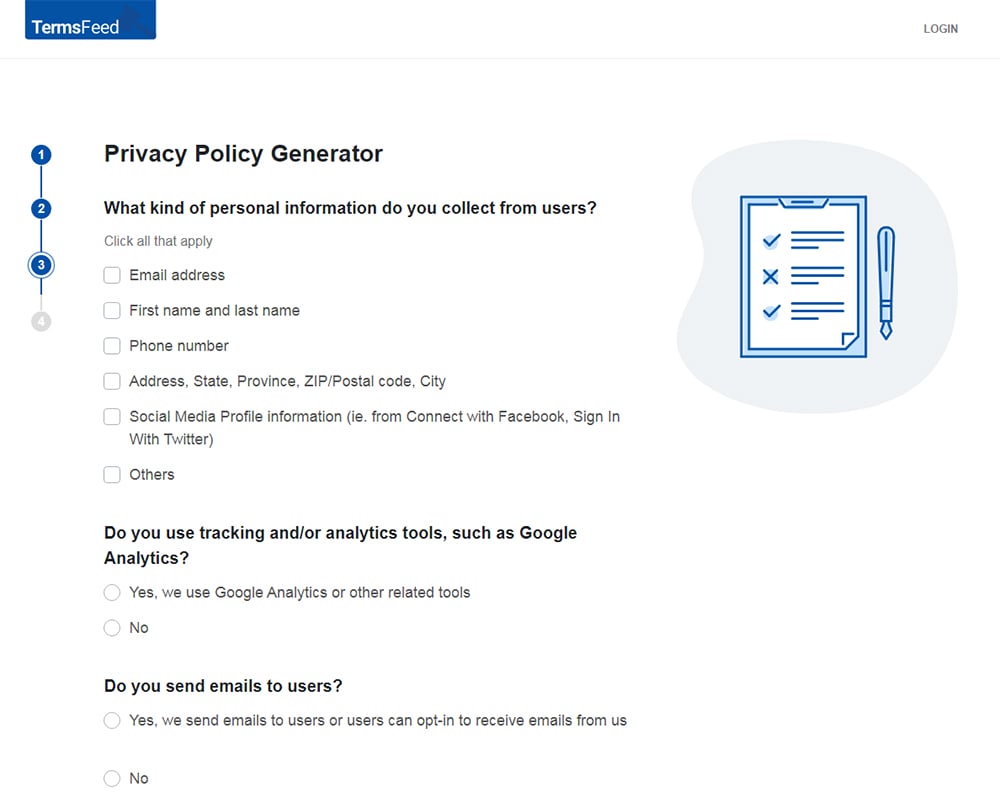

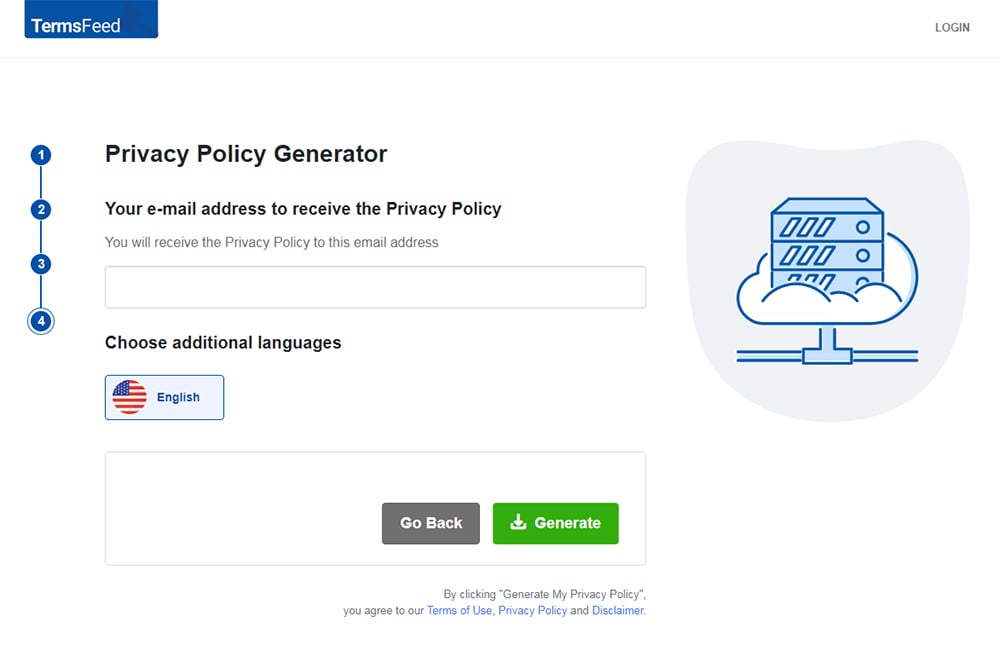

Our Privacy Policy Generator makes it easy to create a Privacy Policy for your business. Just follow these steps:

-

At Step 1, select the Website option or App option or both.

-

Answer some questions about your website or app.

-

Answer some questions about your business.

-

Enter the email address where you'd like the Privacy Policy delivered and click "Generate."

You'll be able to instantly access and download your new Privacy Policy.

- 1. Chapter 1: General Provisions (Articles 1-4)

- 1.1. Article 1 - Subject-Matter and Objectives

- 1.2. Article 2 - Material Scope

- 1.3. Article 3 - Territorial Scope

- 1.4. Article 4 - Definitions

- 2. Chapter 2: Principles (Articles 5-11)

- 2.1. Article 5 - Principles Relating to Processing of Personal Data

- 2.2. Article 6 - Lawfulness of Processing

- 2.3. Article 7 - Conditions for Consent

- 2.4. Article 8 - Conditions Applicable to Child's Consent in Relation to Information Society Services

- 2.5. Article 9 - Processing of Special Categories of Personal Data

- 2.6. Article 10 - Processing of Personal Data Relating to Criminal Convictions and Offences

- 2.7. Article 11 - Processing Which Does Not Require Identification

- 3. Chapter 3: Rights of the Data Subject (Articles 12-23)

- 3.1. Article 12 - Transparent Information, Communication and Modalities for the Exercise of the Rights of the Data Subject

- 3.2. Article 13 - Information to Be Provided Where Personal Data Are Collected from the Data Subject

- 3.3. Article 14 - Information to Be Provided Where Personal Data Have Not Been Obtained from the Data Subject

- 3.4. Article 15 - Right of Access By the Data Subject

- 3.5. Article 16 - Right to Rectification

- 3.6. Article 17 - Right to Erasure ('Right to Be Forgotten')

- 3.7. Article 18 - Right to Restriction of Processing

- 3.8. Article 19 - Notification Obligation Regarding Rectification or Erasure of Personal Data or Restriction of Processing

- 3.9. Article 20 - Right to Data Portability

- 3.10. Article 21 - Right to Object

- 3.11. Article 22 - Automated Individual Decision-making, Including Profiling

- 3.12. Article 23 - Restrictions

- 4. Chapter 4: Controller and Processor (Articles 24-43)

- 4.1. Article 24 - Responsibility of the Controller

- 4.2. Article 25 - Data Protection By Design and By Default

- 4.3. Article 26 - Joint Controllers

- 4.4. Article 27 - Representatives of Controllers or Processors Not Established in the Union

- 4.5. Article 28 - Processor

- 4.6. Article 29 - Processing Under the Authority of the Controller or Processor

- 4.7. Article 30 - Records of Processing Activities

- 4.8. Article 31 - Cooperation with the Supervisory Authority

- 4.9. Article 32 - Security of Processing

- 4.10. Article 33 - Notification of a Personal Data Breach to the Supervisory Authority

- 4.11. Article 34 - Communication of a Personal Data Breach to the Data Subject

- 4.12. Article 35 - Data Protection Impact Assessment

- 4.13. Article 36 - Prior Consultation

- 4.14. Article 37 - Designation of the Data Protection Officer

- 4.15. Article 38 - Position of the Data Protection Officer

- 4.16. Article 39 - Tasks of the Data Protection Officer

- 4.17. Article 40 - Codes of Conduct

- 4.18. Article 41 - Monitoring of Approved Codes of Conduct

- 4.19. Article 42 - Certification

- 4.20. Article 43 - Certification Bodies

- 5. Chapter 5: Transfers of Personal Data to Third Countries or International Organisations (Articles 44-50)

- 5.1. Article 44 - General Principle for Transfers

- 5.2. Article 45 - Transfers on the Basis of an Adequacy Decision

- 5.3. Article 46 - Transfers Subject to Appropriate Safeguards

- 5.4. Article 47 - Binding Corporate Rules

- 5.5. Article 48 - Transfers or Disclosures Not Authorised By Union Law

- 5.6. Article 49 - Derogations for Specific Situations

- 5.7. Article 50 - International Cooperation for the Protection of Personal Data

- 6. Chapter 6: Independent Supervisory Authorities (Articles 51-59)

- 6.1. Article 51 - Supervisory Authority

- 6.2. Article 52 - Independence

- 6.3. Article 53 - General Conditions for the Members of the Supervisory Authority

- 6.4. Article 54 - Rules on the Establishment of the Supervisory Authority

- 6.5. Article 55 - Competence

- 6.6. Article 56 - Competence of the Lead Supervisory Authority

- 6.7. Article 57 - Tasks

- 6.8. Article 58 - Powers

- 6.9. Article 59 - Activity Reports

- 7. Chapter 7: Cooperation and Consistency (Articles 60-76)

- 7.1. Article 60 - Cooperation Between the Lead Supervisory Authority and the Other Supervisory Authorities Concerned

- 7.2. Article 61 - Mutual Assistance

- 7.3. Article 62 - Joint Operations of Supervisory Authorities

- 7.4. Article 63 - Consistency Mechanism

- 7.5. Article 64 - Opinion of the Board

- 7.6. Article 65 - Dispute Resolution By the Board

- 7.7. Article 66 - Urgency Procedure

- 7.8. Article 67 - Exchange of Information

- 7.9. Article 68 - European Data Protection Board

- 7.10. Article 69 - Independence

- 7.11. Article 70 - Tasks of the Board

- 7.12. Article 71 - Reports

- 7.13. Article 72 - Procedure

- 7.14. Article 73 - Chair

- 7.15. Article 74 - Tasks of the Chair

- 7.16. Article 75 - Secretariat

- 7.17. Article 76 - Confidentiality

- 8. Chapter 8: Remedies, Liability and Penalties (Articles 77-84)

- 8.1. Article 77 - Right to Lodge a Complaint with a Supervisory Authority

- 8.2. Article 78 - Right to an Effective Judicial Remedy Against a Supervisory Authority

- 8.3. Article 79 - Right to an Effective Judicial Remedy Against a Controller or Processor

- 8.4. Article 80 - Representation of Data Subjects

- 8.5. Article 81 - Suspension of Proceedings

- 8.6. Article 82 - Right to Compensation and Liability

- 8.7. Article 83 - General Conditions for Imposing Administrative Fines

- 8.8. Article 84 - Penalties

- 9. Chapter 9: Provisions Relating to Specific Processing Situations (Articles 85-91)

- 9.1. Article 85 - Processing and Freedom of Expression and Information

- 9.2. Article 86 - Processing and Public Access to Official Documents

- 9.3. Article 87 - Processing of the National Identification Number

- 9.4. Article 88 - Processing in the Context of Employment

- 9.5. Article 89 - Safeguards and Derogations Relating to Processing for Archiving Purposes in the Public Interest, Scientific or Historical Research Purposes or Statistical Purposes

- 9.6. Article 90 - Obligations of Secrecy

- 9.7. Article 91 - Existing Data Protection Rules of Churches and Religious Associations

- 10. Chapter 10: Delegated Acts and Implementing Acts (Articles 92-93)

- 10.1. Article 92 - Exercise of the Delegation

- 10.2. Article 93 - Committee Procedure

- 11. Chapter 11: Final Provisions (Articles 94-99)

- 11.1. Article 94 - Repeal of Directive 95/46/Ec

- 11.2. Article 95 - Relationship with Directive 2002/58/Ec

- 11.3. Article 96 - Relationship with Previously Concluded Agreements

- 11.4. Article 97 - Commission Reports

- 11.5. Article 98 - Review of Other Union Legal Acts on Data Protection

- 11.6. Article 99 - Entry into Force and Application

Chapter 1: General Provisions (Articles 1-4)

Article 1 - Subject-Matter and Objectives

The GDPR:

- Sets out rules about how personal data is processed;

- Protects people's rights and freedoms in relation to personal data;

- Ensures that personal data can move freely within the EU.

Article 2 - Material Scope

The GDPR:

- Applies where data is processed automatically or is part of a filing system;

- Doesn't apply to purely domestic or personal activity;

- Doesn't apply to certain law enforcement activities.

Article 3 - Territorial Scope

The GDPR:

- Applies to any data processing that takes place in the EU (no matter where the person or organization doing the processing is based);

- Applies to anyone:

- Offering goods or services (paid or free) in the EU, or

- Monitoring people's behavior in the EU

Article 4 - Definitions

Key definitions include:

- Personal data - information that can be used to identify an individual.

- Processing - any action taken with personal data.

- Controller - any body or organization that decides how or why personal data is processed.

- Processor - any body or organization that processes personal data for a controller.

- Consent - A statement or affirmative action that shows agreement to having personal data processed. Must be freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous.

Chapter 2: Principles (Articles 5-11)

Article 5 - Principles Relating to Processing of Personal Data

All personal data processing must adhere to six principles, which are the responsibility of the data controller:

- Lawfulness, fairness and transparency;

- Limitation of processing to legitimate purposes;

- Data minimization;

- Accuracy;

- Limitation on time period of storage;

- Integrity and confidentiality.

Article 6 - Lawfulness of Processing

All personal data processing must occur under one of six lawful bases:

- Consent;

- Contract;

- Legal obligation;

- Vital interests;

- Public task;

- Legitimate interests.

Article 7 - Conditions for Consent

Consent must be:

- Freely given;

- Given via a clear, affirmative act (opt-in);

- Easy to withdraw.

Here's how magazine New Scientist invites its users to withdraw their consent in its Privacy Policy:

Article 8 - Conditions Applicable to Child's Consent in Relation to Information Society Services

If you need to process the personal data of a child under the age of 16 for "information society services" and you're relying on consent as your lawful basis for doing this, you need the consent of their parent or carer.

You also need to take reasonable steps to make sure it was actually their parent or carer that consented.

Information society service (ISS) broadly means any online service - apps, websites, games, streaming services.

Article 9 - Processing of Special Categories of Personal Data

Special categories of personal data include information about a person's:

- Race;

- Political views;

- Religion or beliefs;

- Sex life;

- Genetic, biometric or health data;

- Union membership.

You may only process special category data under very specific circumstances, including:

- You have a person's consent in connection with a specific purpose;

- The person's life is at risk;

- You're a not-for-profit organization and can demonstrate that it's in your legitimate interests.

Here's how charity Croydon Citizens' Advice Bureau explains its legitimate interest in processing its users' special category data in its Privacy Policy:

Article 10 - Processing of Personal Data Relating to Criminal Convictions and Offences

You can only process data about people's criminal convictions if:

- You're doing so under the control of an official authority;

- You're authorized to do so under the GDPR-compliant law of an EU Member State.

Article 11 - Processing Which Does Not Require Identification

If your reasons for processing personal information don't require you to actually know whose personal data you're processing, the GDPR doesn't require you to find out.

If you don't know whose personal data you're processing, you should inform the subjects that you don't have enough information to identify them. Articles 15 to 20 won't apply unless the subjects can provide you with extra information that allows you to identify them.

Chapter 3: Rights of the Data Subject (Articles 12-23)

Article 12 - Transparent Information, Communication and Modalities for the Exercise of the Rights of the Data Subject

You need to help your users exercise their data rights. As a data controller, you need to provide information about your data processing activities if requested. When you do so, the information must be:

- Concise;

- Transparent;

- Easy to access;

- Using clear and plain language.

You need to respond to such requests:

- Within one month (or up to three months where necessary);

- Free of charge.

You can ask your users for additional information in order to confirm their identity if you have reasonable doubts of the identity of the person making the request..

You can refuse to facilitate your users' data rights or charge a reasonable fee if their requests are manifestly unfounded or excessive.

Here's how the British Library invites its users to exercise their data rights:

Article 13 - Information to Be Provided Where Personal Data Are Collected from the Data Subject

Where you've collected personal data from your users, you need to provide information at the time that you collect the data. This includes information about:

- Your company contact details;

- How and why you collect their personal data;

- Their data rights.

This is essentially a requirement that you create a Privacy Policy and draw your users' attention to it when they give you their personal data.

Here's how The Guardian explains its reasons for processing their users' personal data in its Privacy Policy:

Article 14 - Information to Be Provided Where Personal Data Have Not Been Obtained from the Data Subject

Where you've obtained personal data about a person that hasn't been provided to you by that person, you need to provide certain information to them within one month. This includes transparent information about:

- Your company;

- What company the data was obtained from;

- How and why you obtained their personal data;

- What categories of data you obtained;

- How long the data will be stored;

- Their data rights (including but not limited to withdrawing consent, lodging complaints, the right to erasure, etc.).

This is essentially a requirement that you make your Privacy Policy available to anyone whose personal data you're processing and provide it as soon as possible.

Article 15 - Right of Access By the Data Subject

People have a right to request information from data controllers about any of their personal data that the controller is having processed. This includes:

- Confirmation that you're processing their data;

- Any of the sorts of information referred to in your Privacy Policy (but specific to them), such as the categories of personal data being processed, why the processing is occurring, how the personal data is collected, etc.).

When this information is requested, the controller must provide a copy free of charge.

Article 16 - Right to Rectification

People have a right to request that data controllers correct any inaccuracies about them in the personal data they've collected. If the data about them is incomplete, they can provide further information so that it can be complete.

Article 17 - Right to Erasure ('Right to Be Forgotten')

People can request that data controllers erase their personal data under certain circumstances, including:

- If it's no longer need for the reasons it was collected;

- If they've withdrawn consent, and there's no other lawful basis for processing it;

- If it's being processed unlawfully;

Under certain circumstances, data controllers can refuse to erase data, including:

- If you can rely on your freedom of expression and information;

- If you're legally obligated to process this personal data;

- If you need the data for public interest or statistical purposes, or for scientific or historical research;

- If you need it for a legal claim.

Article 18 - Right to Restriction of Processing

People can request that data controllers stop processing their personal data in particular ways under certain circumstances, including:

- If your user makes a request for rectification, objection or erasure, and you need time to consider this;

- If you've been processing the data unlawfully but your user doesn't want you to erase it.

Article 19 - Notification Obligation Regarding Rectification or Erasure of Personal Data or Restriction of Processing

When your users have requested that you rectify or erase their personal data, or that you restrict your processing of their personal data, you must also communicate this to each party that you've shared the data with.

You must also inform the data subject about these recipients, unless it requires a disproportionate effort.

Article 20 - Right to Data Portability

People have the right to request a copy of their personal data that has been provided to a data controller. This data should be provided in a format that allows them to transfer it to another data controller. You should carry out this transfer for them, if possible.

Article 21 - Right to Object

Your users have the right to object to your processing of their data. You can refuse to comply with certain objections if your legitimate interests outweigh the rights of your user. Your users have an absolute right to object to receiving direct marketing, and you cannot refuse to comply with this objection.

Article 22 - Automated Individual Decision-making, Including Profiling

If your company makes automated decisions about its users, your users may have grounds to object to this. This includes where those decisions have serious consequences for your users, equivalent to legal effects.

Under certain conditions, you can refuse to comply with this objection, for example:

- If the processing is necessary under a contract or potential contract;

- You're authorized to process personal data in this way by the GDPR-compliant law of an EU Member State.

- Your user consented to this type of processing.

Article 23 - Restrictions

The EU or Member States of the EU can pass laws that restrict the data rights described at Articles 12-22 and 34. There are several reasons this might be allowed, including:

- National security;

- Reasons connected with criminal justice;

- Protecting rights and freedoms.

Any such law must refer to how it deals with certain relevant matters, including:

- The categories of personal data it affects;

- Any risks it poses to people's rights;

- How people might be informed about the restriction.

Chapter 4: Controller and Processor (Articles 24-43)

Article 24 - Responsibility of the Controller

It's the data controller's responsibility to make sure that processing of personal data is compliant with the GDPR.

Article 25 - Data Protection By Design and By Default

The data controller must put in place appropriate data protection measures and safeguards that adhere to privacy principles such as data minimization and purpose limitation. These need to be built into data processing systems by default.

Article 26 - Joint Controllers

Where two or more data controllers determine jointly how and why to process personal data, they can decide between themselves their respective responsibilities for complying with rules set out in the GDPR.

People can still exercise their data rights against any of the data controllers in this arrangement.

Article 27 - Representatives of Controllers or Processors Not Established in the Union

Where a data controller or processor is based outside of the EU, it must normally designate someone to represent them in the EU. This person will be the first point of contact for GDPR-related queries.

This isn't necessary if the data controller or processor is only processing non-special category data occasionally, or is a public body.

Article 28 - Processor

Data controllers may only appoint data processors who can demonstrate that they're GDPR-compliant.

A data processor may only appoint other data processors with the written permission of their data controller.

A data processor must inform their data controller of any changes to the processing they've been hired to do.

Data controllers must have a legally binding contract with their data processors. This contract must contain certain clauses relating to GDPR compliance. This contract also applies to any subcontractors hired by the data processors. If the subcontractors fail to carry out their duties under the contract, the data processor will be held liable.

Article 29 - Processing Under the Authority of the Controller or Processor

Unless legally obligated to do so, the data processor may not process personal data without the data controller's permission. The data must be processed according to instructions by the controller.

Article 30 - Records of Processing Activities

If you're a data controller or data processor, you must keep a record of your data processing activities. This record must contain certain information, including information about:

- Your company;

- The personal data you're processing and for what purposes;

- Your security measures.

You don't need to do this if your company employs fewer than 250 people unless:

- The processing is likely to result in a risk to the rights and freedoms of the data subjects, or

- The processing is not occasional, or

- The processing includes special categories of data or data relating to criminal convictions and offenses.

Article 31 - Cooperation with the Supervisory Authority

All data controllers and data processors (i.e. anyone who is subject to the GDPR) must cooperate with supervisory authorities. These are data protection authorities set up in each Member State to enforce the GDPR.

Article 32 - Security of Processing

Data controllers and data processors must implement certain security measures. These measures need to be at a level that's appropriate for the risk to the data and should consider the costs of implementation against the risk.

Security measures may include:

- Encrypting personal data;

- Ensuring confidentiality;

- Regularly testing security systems.

Article 33 - Notification of a Personal Data Breach to the Supervisory Authority

If you're a data controller and you suffer a personal data breach, you need to report it to the relevant supervisory authority as soon as possible, providing information about your company, the nature of the breach and its likely consequences.

This needs to take place within 72 hours at the most. Any later, and you explain the reasons for the delay.

Data breaches need to be documented.

When the data breach is unlikely to result in a risk to the data subjects, the breach need not be reported.

Data processors need to inform their data controllers of a breach as soon as possible after it occurs.

Article 34 - Communication of a Personal Data Breach to the Data Subject

If you suffer a high-risk data breach which is likely to have a highly significant impact on your users, you must communicate it to your users directly, without delay.

Using simple language, you must provide your users with information about your company, the nature of the breach and its likely consequences.

You might not have to do this if:

- You've encrypted the data;

- After the breach, you took action which successfully negated the risk to your users;

- It would be too difficult to contact each user directly. In such a case you can contact all of your users publicly instead.

Article 35 - Data Protection Impact Assessment

If you're engaging in high-risk data processing using new technologies, you might need to run an assessment to evaluate the potential impact on your users. This will be necessary, for example, if you're:

- Engaged in certain types of automated decision-making;

- Processing special category or criminal record data;

- Monitoring a public area.

This assessment should provide information about certain matters, including the nature of the processing you're planning to do and how you've mitigated against the risks involved.

You might need to consult with your users when you're carrying out the assessment. If you have a data protection officer, you should consult with this individual.

You should review your assessment regularly.

Article 36 - Prior Consultation

If you've carried out a data impact assessment and it looks as though the processing you're planning to do will be particularly high-risk, you'll need to consult with your supervisory authority before proceeding.

You need to provide certain information to your supervisory authority. This includes information about the nature of the processing you're planning to do, and how you've mitigated against the risks involved.

If it looks like the processing you're planning might infringe the GDPR, the supervisory authority must offer advice within eight weeks (fourteen weeks if the processing is particularly complicated).

Article 37 - Designation of the Data Protection Officer

Under certain conditions, your organization might need to designate a data protection officer. For example, if it's:

- A public authority (except courts);

- Monitoring people on a large scale;

- Processing a lot of special category or criminal record data.

One data protection officer might serve several public authorities.

This can be an existing member of staff or a contractor, but they must be a data protection expert.

If you have a data protection officer, you must publish their contact details (such as in your Privacy Policy).

Article 38 - Position of the Data Protection Officer

The data protection officer must be involved in all aspects of data protection in your organization. You need to support them and ensure they can access any necessary training.

You must not tell the data protection officer how to carry out their data protection responsibilities. They should report to the highest level of management in your organization. They may do other jobs within your organization, so long as there is no conflict of interest with their duties as data protection officer.

Article 39 - Tasks of the Data Protection Officer

The data protection officer has various responsibilities, including:

- Advising their organization on data protection law;

- Monitoring GDPR compliance;

- Cooperating with the supervisory authority.

Article 40 - Codes of Conduct

EU Member States should encourage certain bodies, such as associations of small or medium-sized enterprises, to draw up codes of conduct which instruct their members on how to comply with the GDPR.

These codes of conduct should include information about things such as:

- Data protection principles;

- Users' data rights;

- Data breach protocols.

Such codes of conduct should be submitted to the supervisory authority for approval. The European Commission can decide if a code of conduct has general validity throughout the whole of the EU.

Article 41 - Monitoring of Approved Codes of Conduct

If accredited to do so by a supervisory authority, certain bodies can monitor compliance with codes of conduct. Such a body will need to meet certain criteria, including:

- It has expertise in the subject-matter of the code;

- It has systems in place to ensure compliance and handle complaints;

- It is suitably independent.

This accreditation body can exclude or suspend organizations who don't comply with the code of conduct, so long as they let the supervisory authority know.

Article 42 - Certification

EU Member States, together with various institutions, must encourage voluntary certification schemes. These schemes will allow organizations to demonstrate their GDPR compliance.

These schemes should provide a clear and transparent process by which organizations can earn certificates, seals and marks that verify their good data protection practices. Such awards should only be valid for up to three years, at which point they'll be subject to renewal.

Article 43 - Certification Bodies

Certificates designed to verify GDPR compliance should only be issued by bodies that are themselves accredited by either the supervisory authority or the European co-operation for Accreditation (EA).

A certification body must fulfill certain requirements, including having:

- Demonstrated that it is independent;

- Set up systems to regulate its certification schemes;

- Set up systems to handle complaints about the organizations it certifies.

Supervisory authorities have the ability to revoke the powers of certification bodies.

Chapter 5: Transfers of Personal Data to Third Countries or International Organisations (Articles 44-50)

Article 44 - General Principle for Transfers

Anyone transferring personal data from the EU to a third country or an international organization must comply with the conditions set out in Chapter 5 of the GDPR (Articles 44 to 50).

Article 45 - Transfers on the Basis of an Adequacy Decision

If the European Commission has given approval to a third country's data processing practices, affirming that they are adequate, you can transfer personal data from the EU to this country.

The European Commission will consider certain factors in deciding whether to approve a third country, including:

- The country's record on human rights;

- The existence and effectiveness of a supervisory authority;

- Whether the country is party to international agreements on data protection.

The European Commission will review its approval of third countries every four years. It will maintain a list of approved third countries.

Article 46 - Transfers Subject to Appropriate Safeguards

If a third country isn't approved by the Commission, you can still transfer personal data to that third country from the EU, even without the permission of your supervisory authority - but you need to put certain safeguards in place. Such safeguards include:

- A legally binding agreement between public bodies;

- Binding corporate rules of the sort covered in Article 47 of the GDPR;

- An approved code of conduct of the sort covered in Article 40 of the GDPR.

You can also transfer personal data from the EU to a non-approved third country if you have certain contractual clauses or provisions, but you'll need permission from your supervisory authority for this.

Article 47 - Binding Corporate Rules

A company can enact certain rules that will allow it to transfer data to third countries that haven't been approved by the European Commission. Such rules need to be legally binding on anyone who is involved in the data processing operation and must confer rights on the people whose data is being transferred out of the EU.

Binding corporate rules need to specify various information, including:

- Who will be affected by the data transfer;

- What types of personal data are being transferred;

- How the information about the data transfer will be communicated.

A supervisory authority can approve a company's rules if they fulfill certain criteria. If its rules are approved by one supervisory authority, a company doesn't need to approach each other supervisory authority in every Member State in which it operates.

Article 48 - Transfers or Disclosures Not Authorised By Union Law

If a court in a third country rules that personal data should be transferred out of the EU, this will only be enforceable if there's an international agreement between the third country and the EU or an EU Member State. This is in addition to any of the other allowable circumstances for third country data transfers, as set out between Articles 44-50 of the GDPR.

Article 49 - Derogations for Specific Situations

Under certain circumstances, it's possible to transfer personal data to a non-approved third country, even if you haven't put appropriate safeguards (under Article 45) or binding corporate rules (under Article 46) in place.

This can only happen under certain circumstances, including where:

- The person whose data is being transferred has specifically consented to it, after being informed of the risks;

- The transfer is necessary in the course of a legal claim;

- The transfer is necessary in the course of a contract between the data subject and controller;

- The transfer is necessary to save the person's life, and they're unable to consent to it.

Article 50 - International Cooperation for the Protection of Personal Data

The European Commission and the supervisory authorities will seek to establish good relations with third countries to help them develop good data protection practices.

Chapter 6: Independent Supervisory Authorities (Articles 51-59)

Article 51 - Supervisory Authority

EU Member States must provide a supervisory authority. This is a public body which monitors how the GDPR is being applied. The supervisory authorities of different EU Member States must cooperate with one another.

Article 52 - Independence

Supervisory authorities take instruction from no-one and must remain completely independent. Their budget should be made public, and their freedom from state interference must not be infringed upon.

Article 53 - General Conditions for the Members of the Supervisory Authority

Members of supervisory authorities must be appointed by state institutions. They must be suitably qualified and shall only be dismissed under specific conditions.

Article 54 - Rules on the Establishment of the Supervisory Authority

EU Member States must pass various laws in connection with supervisory authorities. These laws must cover certain things, including:

- The qualifications that are required to become a member of a supervisory authority;

- The rules for appointing members;

- The number of terms that a member may serve.

Members of supervisory authorities are bound by professional confidentiality.

Article 55 - Competence

Supervisory bodies must be able and allowed to carry out all the tasks assigned to them by the GDPR - but are not allowed to supervise data processing carried out by courts.

Article 56 - Competence of the Lead Supervisory Authority

If you're carrying out data processing across borders, the supervisory authority of the EU Member State in which you're based (or do most of your processing activity) will be your lead supervisory authority.

Any complaints or allegations of GDPR infringement will be handled by the supervisory authority of the Member State in which the incident occurred. This may or may not be the lead supervisory authority. If it's not the lead supervisory authority, the relevant supervisory authority must inform the lead supervisory authority about the incident. The lead supervisory authority then has three weeks to decide whether it will deal with the incident itself, or let the reporting supervisory authority handle it.

If you're engaged in cross-border data processing, you'll only be communicating with the lead supervisory authority and no other supervisory authorities are allowed to communicate with you.

Article 57 - Tasks

A supervisory authority has certain tasks to carry out in its Member State, including:

- Monitoring and enforcing the GDPR;

- Promoting good data protection practice and making everyone aware of their legal obligations;

- Handling complaints lodged by individuals about the way their personal data has been processed.

Supervisory authorities can't charge for their services, except for where a person is making complaints that are manifestly unfounded or excessive.

Article 58 - Powers

A supervisory authority has certain powers in its Member States, including:

- Investigative powers, such as gaining access to a data controller or processor's premises and equipment;

- Corrective powers, such as issuing warnings and fines where the GDPR has been infringed;

- Advisory powers, such as issuing opinions to the Member State's parliament about data protection issues.

Article 59 - Activity Reports

A supervisory authority must prepare an annual report on its activities, including data about any GDPR infringements it has been made aware of. This report must be made publicly available.

Chapter 7: Cooperation and Consistency (Articles 60-76)

Article 60 - Cooperation Between the Lead Supervisory Authority and the Other Supervisory Authorities Concerned

Lead supervisory authorities must try to work together with other supervisory authorities and reach a mutual agreement where possible. Lead supervisory authorities can ask that other supervisory authorities help each other, and must encourage open and transparent sharing of information.

The lead supervisory authority will publish draft decisions where it needs to take action in relation to a complaint or alleged infringement. Other relevant supervisory authorities can then give their opinions on it. They can raise objections and the decision will be adjusted where appropriate.

Article 61 - Mutual Assistance

Supervisory authorities must help each other implement the GDPR. This includes providing each other with all necessary information.

If a supervisory authority asks another for help, they must receive a response within a month at the latest. Such requests can only be refused under very specific circumstances, including:

- If it's outside of the supervisory authority's powers or abilities;

- If complying with the request would infringe the GDPR.

Article 62 - Joint Operations of Supervisory Authorities

Sometimes supervisory authorities will need to work together on joint operations. For example, when personal data processing is likely to affect people in more than one EU Member State.

A supervisory authority from one EU Member State can grant some of their powers a supervisory authority from another. Staff who are working in a Member State other than their own are liable for any damage they cause in their host Member State.

Article 63 - Consistency Mechanism

The GDPR contains a mechanism for ensuring that it's applied consistently by supervisory authorities across the EU. All supervisory authorities must abide by this consistency mechanism.

Article 64 - Opinion of the Board

The European Data Protection Board (referred to throughout the GDPR as "the Board") is tasked with issuing an opinion where a supervisory authority takes certain actions. These include where a supervisory authority wishes to:

- Approve a code of conduct which covers data processing activities across several EU Member States;

- Authorize certain contractual clauses, which serve as safeguards to allow organizations to transfer data to non-approved third countries;

- Approve binding corporate rules, which allow companies to transfer data to non-approved third countries.

Article 65 - Dispute Resolution By the Board

Under some circumstances where there is a disagreement among supervisory authorities about how to implement the GDPR, the European Data Protection Board can make a binding decision about what should happen.

Article 66 - Urgency Procedure

If an emergency arises and there's a significant risk to people's important personal data, a supervisory authority has the power to adopt temporary laws to prevent or mitigate this risk. These laws can only be in place for a maximum period of three months.

Article 67 - Exchange of Information

The European Commission can pass delegated acts to specify how information is exchanged between supervisory authorities, and between supervisory authorities and the European Data Protection Board. Delegated acts are used to make non-essential changes to existing laws.

Article 68 - European Data Protection Board

The European Data Protection Board is composed of the head of one supervisory authority in each EU Member State, and is represented by its Chair. The European Commission can come to its meetings but isn't allowed to vote.

Article 69 - Independence

The European Data Protection Board takes instruction from no-one and must remain completely independent.

Article 70 - Tasks of the Board

The European Data Protection Board has certain tasks which allow it to ensure consistent application of the GDPR, including:

- Advising the European Commission on proposed amendments to the GDPR;

- Issuing best practice guidelines to help people comply with the GDPR;

- Promoting cooperation between supervisory authorities.

Article 71 - Reports

The European Data Protection Board produces an annual report on data protection. This report is publicly available and shall include recommendations, best practices and practical applications for the GDPR.

Article 72 - Procedure

The European Data Protection Board makes decisions by simple majority vote. It can change its rules or adopt new ones by a two-thirds majority vote.

Article 73 - Chair

The European Data Protection Board elects a chair and two deputy chairs by simple majority vote. They serve a maximum of two five year terms.

Article 74 - Tasks of the Chair

The Chair of the European Data Protection Board has a number of tasks, including:

- Convening meetings of the Board and preparing meeting agendas;

- Notifying relevant supervisory authorities about any decisions its made in resolving their disputes;

- Ensuring the Board performs its duties in a timely fashion.

Article 75 - Secretariat

The European Data Protection Supervisor provides the European Data Protection Board with a secretariat. The Secretariat works exclusively under the instruction of the Chair of the European Data Protection Board. The Secretariat helps provide administrative support to the Board, and is responsible for:

- The Board's day-to-day management;

- Internal and external communications;

- Preparing opinions and decisions.

Article 76 - Confidentiality

Discussions of the European Data Protection Board are confidential where appropriate. Some of the documents submitted to the Board are available to the public under certain conditions.

Chapter 8: Remedies, Liability and Penalties (Articles 77-84)

Article 77 - Right to Lodge a Complaint with a Supervisory Authority

Individuals have the right to lodge a complaint with a supervisory authority. The supervisory authority must keep them informed about the progress of their complaint.

Article 78 - Right to an Effective Judicial Remedy Against a Supervisory Authority

Individuals have the right to take a supervisory authority to court to seek remedies against the authority's decision concerning them. The court will be in whichever EU Member State the supervisory authority is based. An individual might take a supervisory authority to court if it doesn't handle the individual's complaint properly.

Article 79 - Right to an Effective Judicial Remedy Against a Controller or Processor

Individuals have the right to take a data controller or processor to court if the individual feels his rights have been infringed upon due to non-compliance with the GDPR. The court can be either in whichever EU Member State the data controller or processor is based or the EU Member State in which the individual is based.

Article 80 - Representation of Data Subjects

When an individual brings a court case against a supervisory authority, data controller or processor, they have the right to be supported by a not-for-profit organization. This organization should be involved in data protection and have objectives that serve the public interest.

EU Member States must also allow this organization to lodge complaints with supervisory authorities on behalf of individuals.

Article 81 - Suspension of Proceedings

If a Member State court is dealing with a case brought against a data controller or processor and becomes aware that in a different EU Member State, another related case is pending against the same data controller or processor, the first court should contact the second court to confirm this. The second court can then suspend proceedings.

Article 82 - Right to Compensation and Liability

Anyone who has been damaged by an infringement of the GDPR has a right to receive financial compensation from the infringing data controller or processor.

Data controllers who are involved in data processing are responsible for any damage they cause by infringing the GDPR.

Data processors are only responsible for the damage they cause by:

- Infringing those parts of the GDPR that are specifically addressed to data processors;

- Acting against the instructions of their data controller.

Article 83 - General Conditions for Imposing Administrative Fines

Supervisory authorities can fine data controllers and processors for infringing the GDPR. These fines are designed in part to serve as a deterrent.

The supervisory authority takes several factors into account when deciding whether to impose a fine, and how much a fine should be. These factors include:

- The seriousness of the infringement;

- Whether it was intentional or negligent;

- Whether any steps were taken to limit the damage done.

Some infringements attract a fine of a maximum of 10 million euros or 2 percent of a company's annual worldwide turnover - whichever is higher. Examples of such infringements include:

- Breaching the rules around earning children's consent for online services;

- Failing to integrate appropriate data protection mechanisms into a data processing system;

- Failing to submit all necessary information as part of a certification process.

Other infringements attract a fine of a maximum of 20 million euros or 4 percent of a company's annual worldwide turnover - whichever is higher. Examples of such infringements include:

- Failing to properly gain consent where required;

- Failing to follow the rules around processing special category data;

- Not complying with the supervisory authority.

Article 84 - Penalties

In addition to the fines set out in the GDPR, EU Member States must implement a separate system of penalties to deter infringement of the GDPR.

Chapter 9: Provisions Relating to Specific Processing Situations (Articles 85-91)

Article 85 - Processing and Freedom of Expression and Information

EU Member States have to strike a balance between data protection and freedom of expression. This means providing exceptions to certain parts of the GDPR for certain activities of journalists, artists, academics and writers. Member States need to inform the European Commission about such exceptions.

Article 86 - Processing and Public Access to Official Documents

Where personal data forms part of an official document used to carry out a task in the public interest, this personal data might be made available to the general public.

Article 87 - Processing of the National Identification Number

EU Member States can make their own rules when it comes to national identification numbers. However, the national identification number can only be used under appropriate data protection conditions.

Article 88 - Processing in the Context of Employment

EU Member States can make additional rules to protect workers' rights around their personal data. Such rules might relate to a range of issues, including:

- Recruitment;

- Equality and diversity;

- Health and safety.

Article 89 - Safeguards and Derogations Relating to Processing for Archiving Purposes in the Public Interest, Scientific or Historical Research Purposes or Statistical Purposes

Processing for certain purposes is subject to special safeguards such as pseudonymization and data minimization. These purposes are: archiving in the public interest, scientific or historical research, and statistical purposes.

EU Member States can make exceptions to certain data rights when it comes to personal data processing for the purposes above.

Article 90 - Obligations of Secrecy

Sometimes data controllers and processors will obtain personal data that they are obligated to keep confidential. EU Member States can make additional rules when it comes to the power of the supervisory authority to access personal data from data controllers and processors in these circumstances.

Article 91 - Existing Data Protection Rules of Churches and Religious Associations

Some churches and religious groups have their own rules on processing personal data. They can keep these rules, so long as they're GDPR-compliant.

Chapter 10: Delegated Acts and Implementing Acts (Articles 92-93)

Article 92 - Exercise of the Delegation

The GDPR gives the European Commission the power to pass particular delegated acts. Delegated acts are used to make non-essential changes to existing laws. The European Council and Parliament can revoke this power at any time.

Article 93 - Committee Procedure

The European Commission will be assisted by a committee to help it with implementing the GDPR.

Chapter 11: Final Provisions (Articles 94-99)

Article 94 - Repeal of Directive 95/46/Ec

The GDPR replaces an older EU law known as Data Protection Directive. This directive is no longer good law as of May 25, 2018, and any references made to it are now considered to be references to the GDPR.

Article 95 - Relationship with Directive 2002/58/Ec

Another EU law, known as the ePrivacy Directive, set out some rules regarding the protection of personal data in public communications networks. The GDPR doesn't create any further obligations on individuals in addition to those set out in this older directive.

Article 96 - Relationship with Previously Concluded Agreements

Some EU Member States are party to international agreements regarding personal data transfer to third countries. So long as these were concluded before 24 May 2016, they are still in force.

Article 97 - Commission Reports

The European Commission will prepare a report every four years, starting in 2020. This report will be publicly available. The report will focus in particular on issues concerning third country data transfers, cooperation, and consistency. It may contain information that's been requested from supervisory authorities, and give the views of other EU institutions.

The Commission may suggest amending the GDPR in light of this report.

Article 98 - Review of Other Union Legal Acts on Data Protection

The European Commission may suggest amendments to other EU data laws.

Article 99 - Entry into Force and Application

The GDPR applies from 25 May 2018.

Comprehensive compliance starts with a Privacy Policy.

Comply with the law with our agreements, policies, and consent banners. Everything is included.