The California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018 (CCPA) is a privacy law that was passed on June 28, 2018 and took effect on January 1, 2020. It was updated, amended and expanded by the CPRA, which became effective on January 1, 2023.

This law has had a significant impact on consumers and certain businesses.

California has consistently passed laws which aim to protect its residents' privacy, such as the California Online Privacy Protection Act (CalOPPA) and the "Shine the Light" law, and the CCPA (CPRA) is no exception.

This article will explain what this law is, who it applies to, and what steps you need to take to comply.

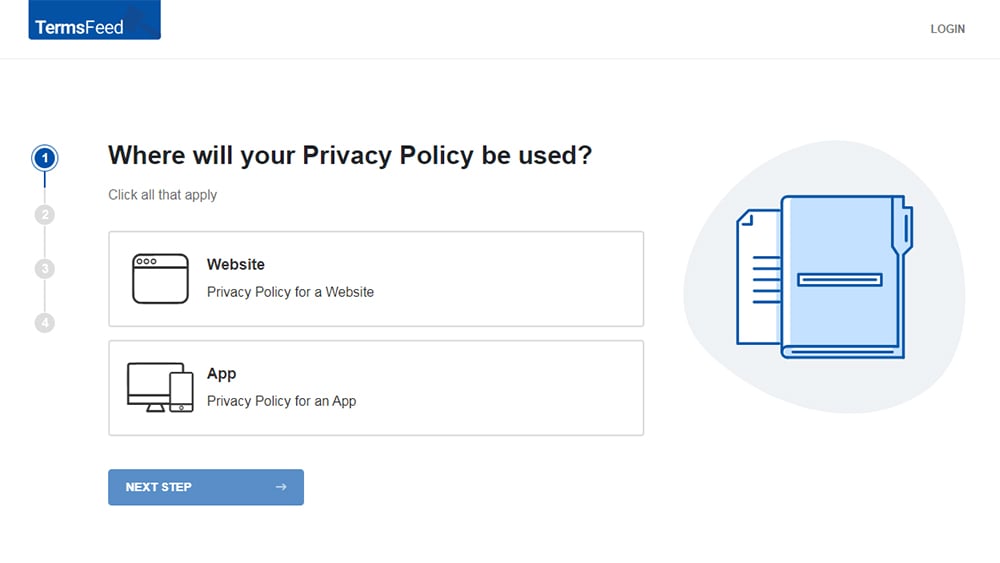

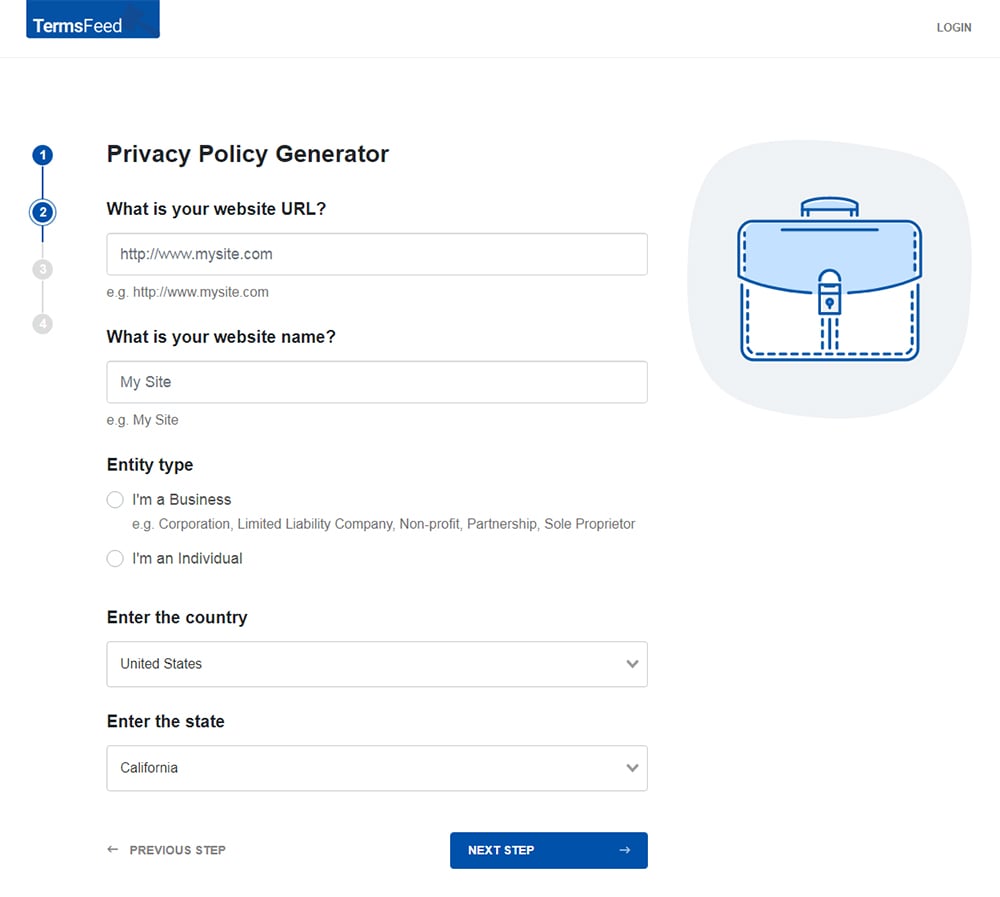

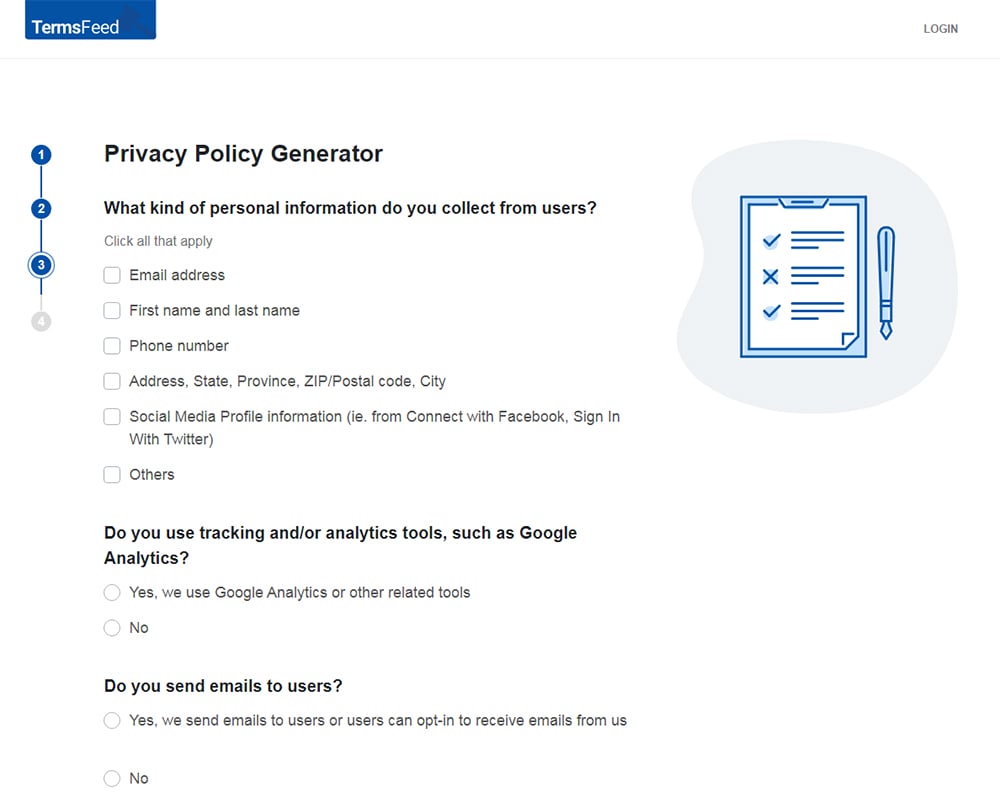

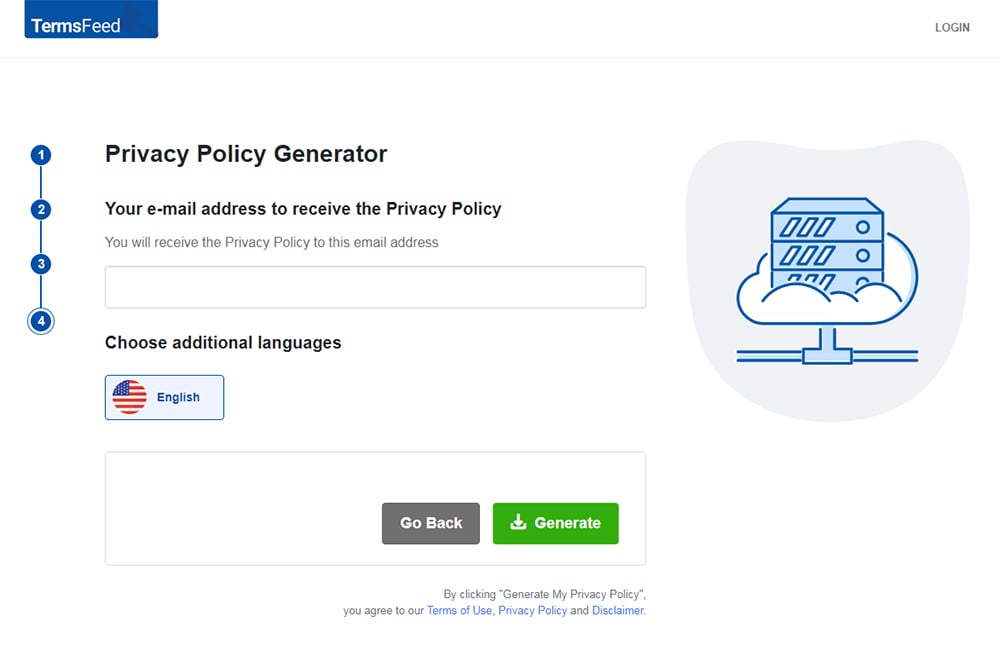

Our Privacy Policy Generator makes it easy to create a Privacy Policy for your business. Just follow these steps:

-

At Step 1, select the Website option or App option or both.

-

Answer some questions about your website or app.

-

Answer some questions about your business.

-

Enter the email address where you'd like the Privacy Policy delivered and click "Generate."

You'll be able to instantly access and download your new Privacy Policy.

- 1. The CCPA/CPRA's Definitions

- 1.1. Business

- 1.2. Consumer

- 1.3. Personal Information

- 1.4. Service Provider

- 2. The CCPA (CPRA) and Privacy Policies

- 3. The CCPA (CPRA) and New Privacy Rights

- 3.1. The Right to Disclosure

- 3.2. The Right to Deletion

- 3.3. The Right to Access

- 3.4. The Right to Opt Out

- 3.4.1. Children's Right to Opt In

- 3.5. The Right to Non-Discrimination

- 4. The CCPA (CPRA) and Fines

- 5. Obligations Under the CCPA (CPRA)

- 6. All U.S. Privacy Laws

Some of the more significant changes that the CCPA (CPRA) introduced to privacy law included:

- Strict transparency obligations on large businesses and data brokers (companies whose primary business activity involves selling personal information),

- A very broad new definition of "personal information" - perhaps the broadest legal definition of the term in the world,

- Several new rights for consumers which businesses must facilitate, and

- A new regime of fines that can be levied on businesses who fail to protect consumers' personal information.

The CCPA/CPRA's Definitions

To understand the types of people and activities the CCPA applies to, it's important to get to grips with the way it defines certain terms.

Business

The CCPA (CPRA) uses the term "business" in a very narrow way.

Where the CCPA (CPRA) refers to a "business," it means a legal entity that has the following characteristics:

- It is operated for profit,

- It does business in California,

- It decides why and how personal information is processed, and

- It has one or more of these characteristics:

- It has a gross revenue of over $25 million per year, or

- It buys, sells, receives or shares personal information from over 100,000 consumers, households or devices per year, or

- It makes half or more of its revenue per year from sharing or selling personal information.

Consumer

The CCPA (CPRA) brings a host of new rights to consumers. "Consumer" means a California resident, as defined at 18 CCR § 17014:

"(1) every individual who is in the State for other than a temporary or transitory purpose, and (2) every individual who is domiciled in the State who is outside the State for a temporary or transitory purpose."

This effectively means anyone who lives in California, even if they are temporarily outside of California, e.g. on vacation. The definition doesn't cover visitors to California.

Personal Information

Personal information is defined in the CCPA (CPRA) as:

"information that identifies, relates to, describes, is capable of being associated with, or could reasonably be linked, directly or indirectly, with a particular consumer or household."

This is a very broad definition, and it's noteworthy that it extends to a "household." Specific examples are given in the CCPA (CPRA). These include a person's:

- Name

- Postal address

- IP address

- Email address

- Social security number

The CCPA (CPRA) also lists general categories of data that must be considered personal information, such as:

- Protected classifications including race, sex, nationality, etc.

- Internet data, including browser history and cookies

- Geolocation data

Note that this is not an exhaustive list of the examples given in the CCPA (CPRA).

Any individual one of these things may not identify a person on its own - but the key word is "indirectly" - if something could be used to identify a person in combination with other information, it should be treated as personal information.

Service Provider

A service provider is a company that "processes information on behalf of a business [...]." The business decides how and why personal Information is processed, and the service provider merely does as instructed by the business. This might be, for example, an email provider like MailChimp, or an eCommerce company like BigCommerce.

If you're familiar with the GDPR, you'll know that it applies to data controllers, who decide how and why personal data is processed - roughly equivalent to "businesses" under the CCPA (CPRA). It also applies to data processors, who carry out processing on behalf of a data controller - like "service providers" under the CCPA (CPRA).

The CCPA (CPRA) and Privacy Policies

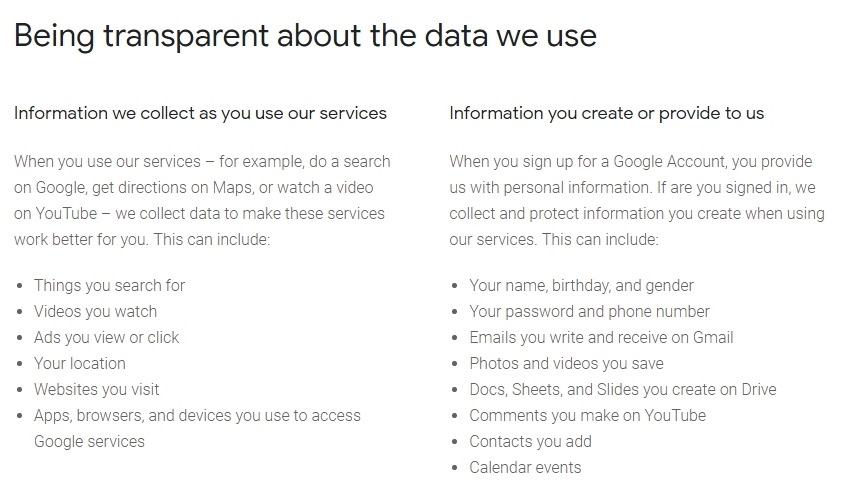

The CCPA (CPRA) requires that businesses reveal certain information in their Privacy Policies.

Before a business collects personal information about a consumer, it must tell them what types of personal information it is collecting, and how it will use each type of personal information it collects.

Here's one of the ways that Google fulfills the first part of this requirement:

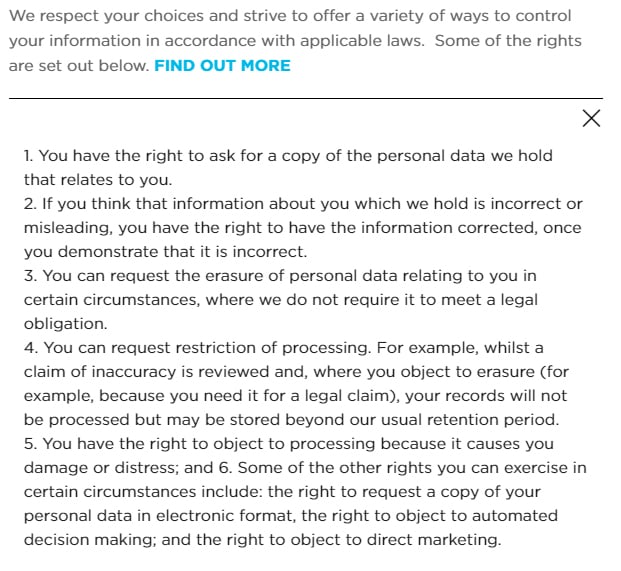

One of the things a business must provide in its Privacy Policy is information about consumers' rights under the CCPA (CPRA), and how to access those rights.

Here's how Workspace sets out its users' rights under the GDPR, and how they can access them:

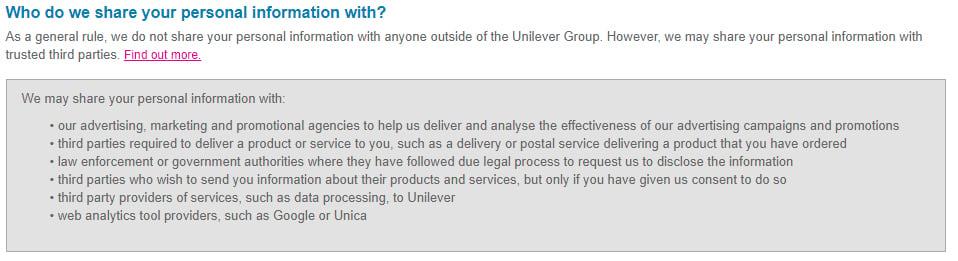

Businesses must also reveal the types of third parties they share personal information with.

Here's how Unilever addresses this in its Privacy Policy:

Where relevant, a business must also explain the following things in its Privacy Policy:

- The commercial reason it collects and sells information

- A link to its "Do Not Sell My Personal Information" page

- Whether it sells consumers' personal information, and if so, what types of personal information it sells

- Where it gets the personal information it collects

The CCPA (CPRA) and New Privacy Rights

The CCPA (CPRA) introduces some new consumer rights. Some of these look a little like the data subject rights under of the GDPR.

The Right to Disclosure

Most of the obligations on businesses under the right to disclosure are discussed above in the "Privacy Policy" section.

One additional requirement on businesses is to:

"Provide a clear and conspicuous link on the business' Internet homepage, titled 'Do Not Sell My Personal Information,'"

This is reminiscent of the obligation on a website operator to provide a "clear and conspicuous" link to their Privacy Policy under CalOPPA.

Some businesses are also required to provide a toll-free phone number to consumers wishing to exercise their CCPA (CPRA) rights.

The Right to Deletion

Those who are familiar with the GDPR's "right to be forgotten" might be a little underwhelmed by the CCPA/CPRA's right to deletion.

The CCPA (CPRA) states that a consumer:

"has the right to request that a business delete any personal information about the consumer which the business has collected from the consumer."

The business also has to contact any service providers with whom they have shared the consumer's personal information and request that they delete the consumer's personal information as well.

Note that the business is only obligated to delete personal information it has collected from the consumer - this doesn't explicitly include personal information it has collected from third parties.

There are also a lot of reasons that a business might not have to carry out this request, for example:

- To carry out a contractual obligation or complete a contract with the consumer

- For security or legal reasons

- For debugging purposes

- If deletion would infringe its freedom of speech or other rights

- If it's legally required to allow access to the information under the California Electronic Communications Privacy Act

- For research in the public interest (if the consumer has consented)

- For internal purposes which the user might reasonably expect the business to carry out

It remains to be seen how meaningful this right will actually end up being, given all these exceptions.

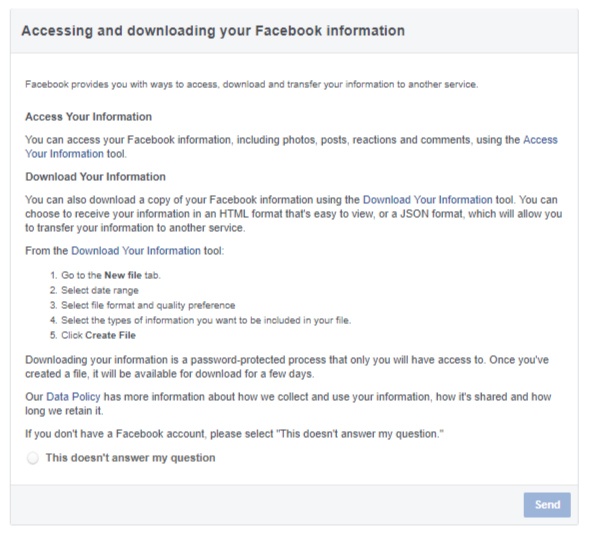

The Right to Access

The CCPA (CPRA) provides consumers with the right to access their personal information. Businesses covered by the CCPA (CPRA) that collect consumers' information must provide the following on request:

- The categories of personal information it collects (e.g. name, phone number, date of birth)

- The specific pieces of personal information it has collected about the consumer

- The categories of sources of the personal information

- The commercial purpose for collecting or selling personal information

- The planned retention time for the collected personal information

- The categories of third parties with whom the business shares personal information

Additionally, where a business sells (or discloses for a commercial purpose) consumers' personal information, the following additional information can be requested by the consumer:

- The categories of personal information it has sold

- The categories of personal information it has disclosed for a commercial purpose

If the business has not done either of these things, it must disclose this.

The information must cover the preceding 12 month period and must be provided in a "readily useable" format (for example, an HTML file), provided free of charge and within 45 days. An additional 45 day extension to this period is possible when reasonably necessary.

The idea is that the consumer can then take their information to another business. Unlike under the GDPR, a business isn't obligated to carry out this transfer itself.

The customer's identity must be verified first. Businesses aren't required to comply more than twice over a 12 month period to the same consumer.

Here's how Facebook complies with a similar obligation under the GDPR:

There is an exception to this obligation - if the consumer only carried out a single transaction with the business, and the business hasn't sold the personal information it acquired from this transaction. In this case, the business isn't obliged to retain this information just in case the consumer requests access to it.

The Right to Opt Out

This is perhaps the CCPA/CPRA's headline provision. Businesses not only have to give consumers the option to forbid the sale of their personal information. they also have to make it easy for them to do this by:

- Providing a link to a "Do Not Sell My Personal Information" page on its homepage, and

- Not requiring consumers to create an account in order to make this request

A business can invite a consumer to opt back in, but only after 12 months of them opting out.

Whilst this right is actually narrower in scope than the right to object and the right to restrict processing under the GDPR, it's possible that the right to opt out will have a bigger impact on businesses. This is because of the conspicuous way that businesses must draw their consumers' attention to this right.

Under the GDPR, a user might stumble upon their "right to object to the means in which personal data is processed" deep in a business's Privacy Policy. Under the CCPA (CPRA), consumers will be invited to tell a business "Do Not Sell My Personal Information" every time they visit its homepage.

That being said, any business that's complying with the GDPR should already have systems in place for carrying out data restriction and objection requests.

Children's Right to Opt In

Rather than a "right to opt out," minors (children) have a "right to opt in." The Privacy Rights for California Minors in the Digital World Act defines a "minor" as a California resident under the age of 18.

There are some specific rules around selling the personal information of minors:

- If a business knows a consumer is a minor aged between 13 and 16, it may not sell their personal information without their consent.

- If a business knows a consumer is under 13, it may not sell their information with their parent or guardian's consent.

- If a business "willfully disregards" a consumer's age, it will be deemed to know their age.

The Right to Non-Discrimination

There's little point in having consumer rights if a business can "punish" consumers who exercise them. In this vein, the CCPA (CPRA) states that:

"A business shall not discriminate against a consumer because the consumer exercised any of the consumer's rights [...]"

The CCPA (CPRA) suggests four ways in which a business might discriminate:

- By refusing to provide goods or services,

- By denying discounts or charging extra for consumers who have exercised their rights,

- By providing a poorer level of service to consumers who have exercised their rights, or

- By threatening a consumer with any of the above if they choose to exercise their rights

There are also a number of CCPA notices that you need to be familiar with when it comes to compliance. We address these notices in our article: CCPA Notices.

The CCPA (CPRA) and Fines

Businesses who infringe the CCPA can be fined up to $7,500 per violation, in the case of intentional violations. Unintentional violations come with fines of up to $2,500. This might sound like a relatively small amount in comparison to the GDPR's eye-watering maximum fine of €20 million or 4 percent of annual global turnover. But this will quickly add up if large-scale or repeated infringements occur.

Consumers can also bring civil claims against businesses on the grounds of :

"unauthorized access and exfiltration, theft, or disclosure [of personal information] as a result of the business' violation of the duty to implement and maintain reasonable security procedures [...]"

The claims must be for amounts between $100 and $750 - or more if the infringement caused an actual loss to the consumer of more than $750. Again, this can quickly add up to millions of dollars, even where a relatively small fraction of California's residents are involved in a security breach.

Obligations Under the CCPA (CPRA)

Whilst the CCPA (CPRA) might not have the same far-reaching implications of the GDPR, it still places a number of new obligations on businesses, and will empower California residents with some important new rights over their personal information.

Certain large businesses and data brokers must:

- Take note of the broad new definition of personal information,

- Provide transparent information and notices about their practices to consumers before they collect personal information from them,

- Update their Privacy Policies to inform consumers about the ways in which they sell personal information,

- Facilitate a consumer's request for the deletion of their personal information,

- Provide a copy of any personal information they hold on consumers on request,

- Provide a way for consumers to opt out from the sale of their personal information,

- Obtain consent from the consumer for the sale of their personal information if the consumer is under the age of 16, or from their parent or guardian in the case of a consumer under the age of 13,

- Not discriminate against consumers in any way if they have exercised their consumer rights under the CCPA (CPRA), and

- Pay a fine if they fail to properly protect consumers' personal information

All U.S. Privacy Laws

Want to read more about privacy laws in the USA? Start here:

| COPPA: Children's Online Privacy Protection Act | Federal law that protects the privacy of children under 13 years of age when online or using a mobile app. |

| HIPAA: Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act | Federal law that protects the privacy of health information of individuals. |

| California CalOPPA: California Online Privacy Protection Act | California law that requires commercial websites to properly display a compliant Privacy Policy. |

| California CCPA: California's Consumer Privacy Act | California law that gives consumers many privacy rights while putting transparency obligations on businesses. |

| California CPRA: California's Privacy Rights Act | California law that expands the CCPA and gives consumers additional rights. |

| Virginia VCDPA: Virginia's Consumer Data Protection Act | Virginia law that allows users to opt out of the sale of their personal data. |

| Maryland PIPA: Maryland's Personal Information Protection Act | Maryland law that requires businesses to keep personal information private and secured. |

| Utah UCPA: Utah's Consumer Privacy Act | Utah law that provides a range of consumer privacy rights, including the right to data portability. |

| Connecticut CTDPA: Connecticut's Personal Data Privacy and Online Monitoring | Connecticut law that places transparency requirements on businesses while granting consumers rights over their personal data. |

| Colorado CPA: Colorado's Privacy Act | Colorado law that grants privacy rights to consumers while dictating how businesses can collect and process personal data. |

| Florida FPPA: Florida's Privacy Protection Act | Florida law that lets consumers control how their personal data is used, while requiring businesses to be more transparent. |

Comprehensive compliance starts with a Privacy Policy.

Comply with the law with our agreements, policies, and consent banners. Everything is included.